Artificial Intelligence: Real Estate's Data Revolution?

The ability to capture, analyze, and act on large amounts of data will turn property development into a never-ending process.

Artificial intelligence will provide landlords with unprecedented amounts of data about their end-users’s needs and behaviors. The best operators will use this data to constantly improve the experience they offer to people who live, work, and shop in their buildings.

To do so, they will have to master new skills and adopt management methodologies that are currently common in the world of software development. These developments will blur the boundary between real estate design, construction, marketing, and operation, and will accelerate the adoption of space-as-a-service.

What is Artificial Intelligence?

Strictly speaking, artificial intelligence does not exist. Human-like entities that can learn, react, and think for themselves across a diversity of scenarios are still quite a way away.

These days, the term Artificial Intelligence is mostly used to describe machine learning algorithms that can find statistical patterns in large amounts of data and infer rules that improve their ability to analyze even more data; image processing algorithms that can “look” at photos or videos and identify specific objects, people, actions, and emotions; and natural language engines that can understand what humans say, respond intelligibly, and improve based on experience.

All of the above involves some sort of learning that allows computers to “act without being explicitly programmed”. Algorithms are not created equal. A basic, “supervised learning” algorithm can infer additional points on a given data set. For example, it can look at the price and size of 200 houses and “guess” the price of other houses within the same area. In other words, when asked “How much does this house cost?”, such an algorithm can infer the answer by looking at data from nearby houses.

“Unsupervised learning” algorithms, in contrast, can identify hidden patterns in data, even without knowing what the “correct answer” has been in previous cases. In fact, such algorithms are often applied to questions that do not have a single right answer. For example, Amazon’s algorithms can look at the books you like and infer what other books, snacks, or electronic gadgets you’re likely to buy. Likewise, Facebook can look at your existing friends and guess who else might be your friend or what type of content you’d enjoy.

Real Estate as we (don’t) know it

Algorithms can be extremely valuable. But they require big and/or diverse data in order to perform effectively. And unlike the digital customer journey on Amazon or Facebook, when it comes to real estate users, data is fragmented or, more likely, non existent.

At the market level, information about acquisitions, leases, and regulation is spread across hundreds of databases. Often, it exists only in written documents or notes or in the minds of local professionals. At the project level, information is siloed across disciplines — site selection, master planning, architecture, interior design, construction, HVAC, property management, marketing, external brokers— and shared haphazardly on a “need to know” basis. A good project manager can do wonders, but it’s an uphill battle.

More importantly, the real estate project lifecycle is made of discrete phases, with clear boundaries between acquisition, development, go-to market (leasing/sales), and operation. While in operation, decision-making is often divided between property managers (day-to-day), asset managers (CapEx, budgets, pricing), and owners or partners that may or may not also be the asset managers. In some cases, lenders have a say on major decisions as well.

And that’s before we even get to the end users. The latter are often ignored completely: For many landlords, the customer is the entity that signs the lease, not the people who spend their waking and/or sleeping hours inside the building. In most office and even residential projects, very little user data is collected about these people — who they are and what they do while they’re here.

In retail and hospitality there is a broader effort to collect real-time user data, but this mostly includes high-level information about traffic, circulation patterns, or personal payment details that users were forced to share. New data collection and analysis tools are often used within the old silos, automating existing processes, crashing against legal concerns and old habits, and used by employees who lack the skills to put them to good use. Retail market leaders are still in the early stages of leveraging user data in a systematic way.

The Development Continuum

Things are different in the world of software. Development is never complete. Product Managers are responsible for “understanding customer requirements, defining and prioritizing them, and working with the engineering team to build them”. They also work with the sales and marketing team and report back to management to reconcile market demand with financial and other constraints.

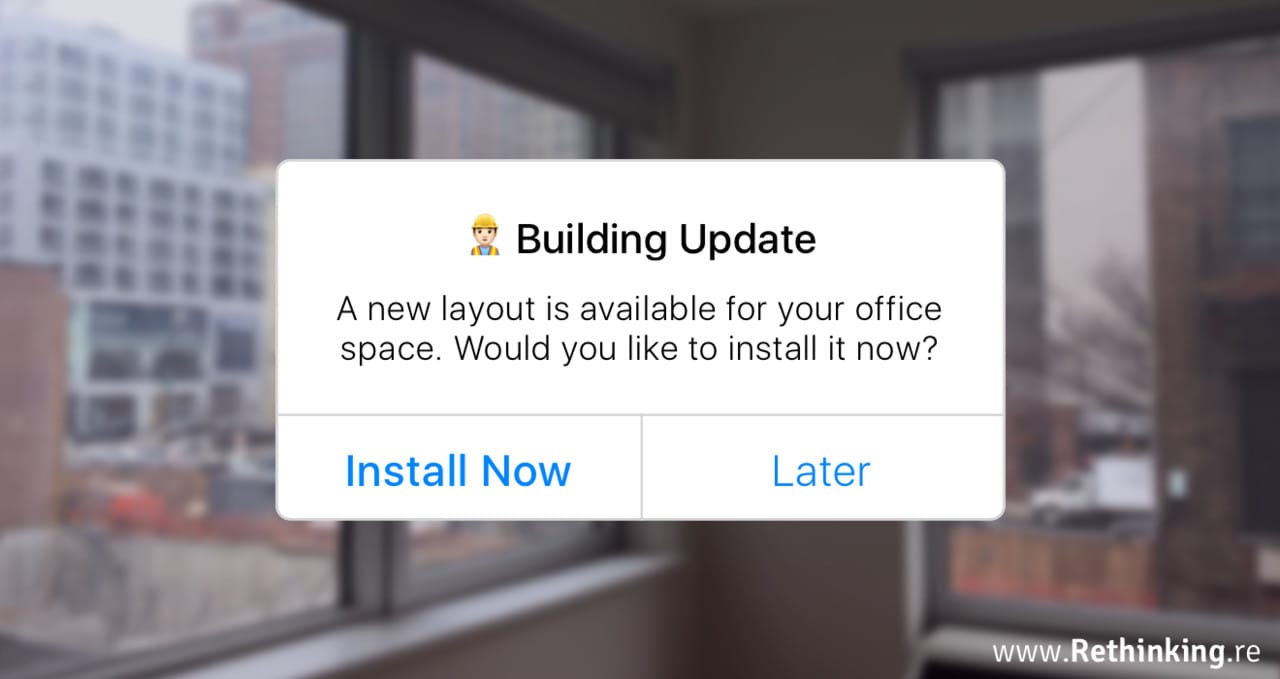

Product Managers set strategy and define a roadmap for product improvements —and overhauls—based on user feedback and usability data. Features and design elements are constantly tweaked to make the overall experience better for users and aligned with the business’s broader goals. Most importantly, Product Managers are involved throughout the product’s lifetime, not just in its initial development phase. They work in design or development sprints to constantly test and deploy product improvements.

But real estate is not software. Buildings are not web sites and visitors are not virtual: They do not accept “cookies”, share their IP address, log in, or provide data simply by “showing up”. Even if more data were available, the product itself is very difficult to change — breaking walls and breaking leases is expensive.

We can sprint, and you can’t hide

But what if there were no walls and no leases? A growing percentage of retail, office, and residential space is offered on short-term, flexible basis and includes a growing number glass partitions, multipurpose spaces, and movable fixtures. More importantly, customer experience within real estate projects is increasingly driven by software and services, leaving plenty of room for ongoing improvements based on real-time data.

And when it comes to data, real estate is in a position to get it all. Artificial Intelligence can scan security cameras to figure out what users bring into into the building, who they’re talking to, what they are talking about, and what makes them happy or sad. It can even infer their IQ and political opinions, and the cost of their clothes.

AI can then use this data to optimize the way office or hospitality space is laid out, and figure out who should sit next to whom. And this is before even looking at data from sensors and IoT devices measuring anything from air quality to toilet paper consumption.

In 5 years, it’s not unlikely that the world’s best real estate operators will know more about their “users” than any web site ever did.

Real implications

These changes to the way real estate assets are managed and designed will have a meaningful impact on end users. They will have an even more meaningful impact on real estate companies and the structure of the industry.

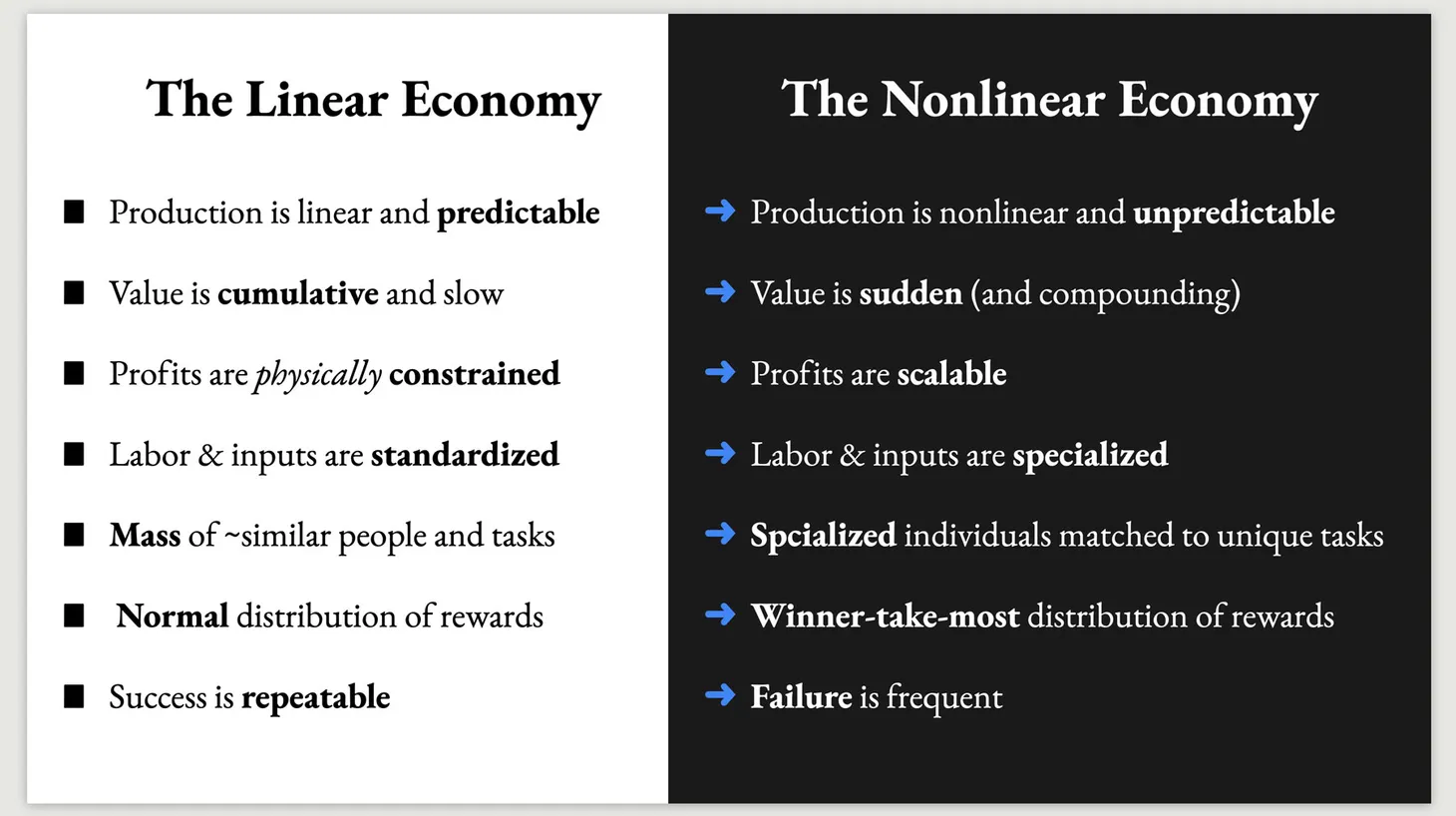

Assets will have to be constantly adjusted and reinvented, making them more like proper businesses and less like stable stores of value. Managing assets will become increasingly specialized, requiring mastery of new tools and operational methods. Most likely, market leaders will develop (or acquire) proprietary tools — both hardware and software. These will favor those who can operate at scale and drive the industry towards consolidation.

More broadly, the never-ending development process would blur the lines between design, construction, operation, marketing, and leasing. The best companies will have all these capabilities in-house, allowing them to constantly iterate and benefit from synergies and network effects that are not available to smaller or unintegrated operators.

The increasing complexity of operating an office or residential space will also blur the boundaries between landlords and tenants. It will be increasingly difficult for tenants to handle their own fit out and master the various tools required to manage their space. This, in turn, will drive more and more tenants to seek turnkey, space-as-a-service solutions —augmenting other demographic and economic trends that already discourage ownership and long leases.

In the coming months, we will explore specific examples of how these dynamics are already emerging in different markets, as well as the second-order effects of other AI-powered technologies such as autonomous vehicles, intuitive design, and virtual reality.

Dror Poleg Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.