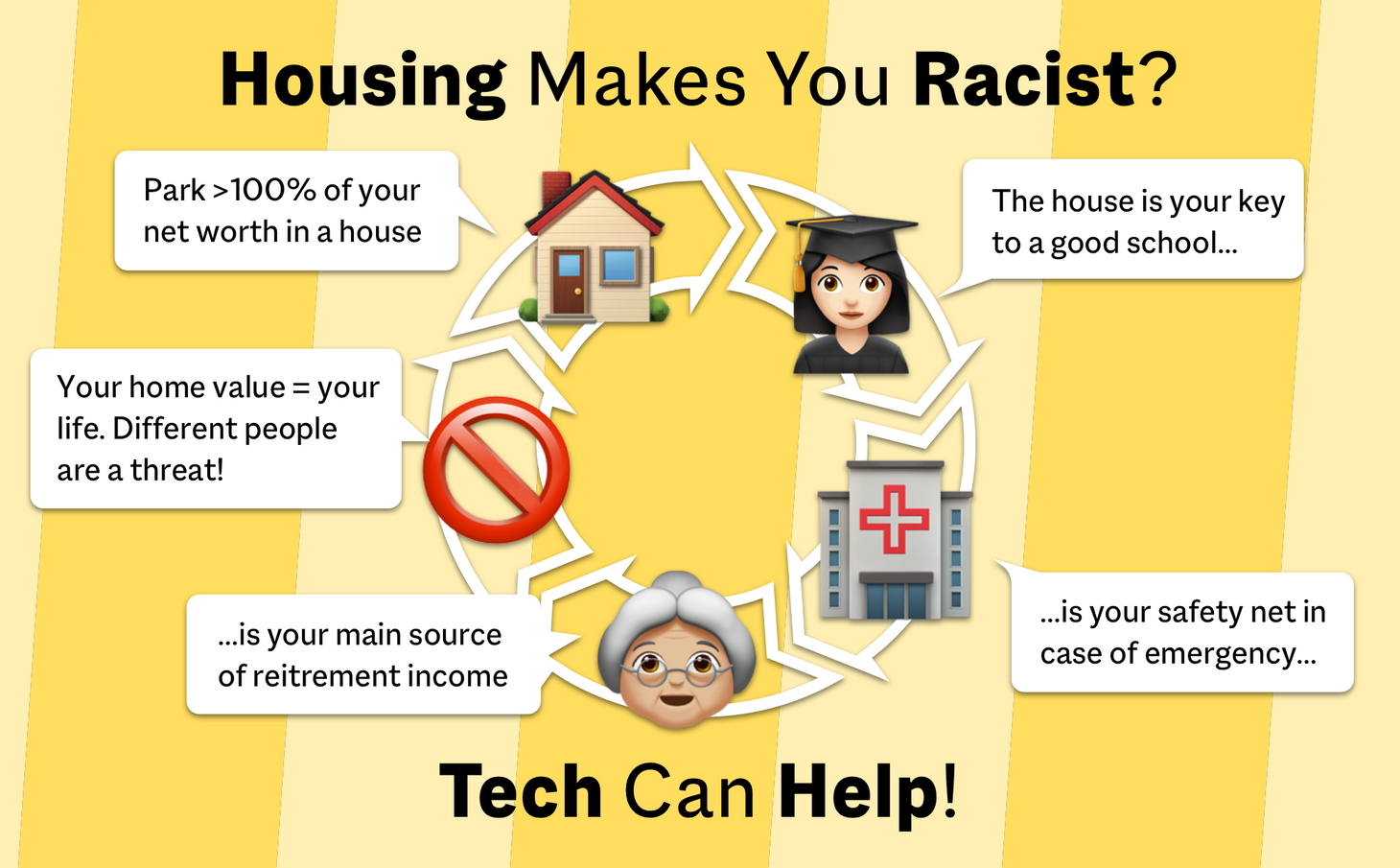

Housing makes you racist. Tech can help.

America's residential system incentivizes people to act like bigots. Technology offers hope — and a few more reasons to worry.

(This article was originally published in July 2020. I recently reposted it.)

US GDP shrank by a whopping 33% in Q2 2020. Almost 30 million Americans reported they’d not had enough to eat during the middle of July. But the stock market is near its all-time high, and the homeownership rate just made its biggest jump ever, reaching a level not seen since 2008.

Amid a global pandemic, racial tensions, antitrust hearings, and a diplomatic crisis with China, President Trump found time to tweet about housing:

I am happy to inform all of the people living their Suburban Lifestyle Dream that you will no longer be bothered or financially hurt by having low income housing built in your neighborhood...

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) July 29, 2020

Why is the president so excited about the "Suburban Lifestyle Dream"? Because suburban housing is the key to the behavior of America's middle class. It causes people to do things that they otherwise wouldn't. It causes people to act against their stated values.

One's house is a focal point of anxiety. And anxiety is the currency of American politics in 2020. What makes houses so important?

The net worth of most middle-class Americans is heavily dependent on the value of their homes. The home of a family with a net worth of $1 million constitutes, on average, about 50% of its net worth.

Most homeowners also have a mortgage. Mortgages make up about two-thirds of all household liabilities. This type of debt is currently at record levels.

Owning a home has been the primary engine of wealth creation in the United States over the past 70 years. Historically, the impact of homeownership extended across generations, meaning that if your grandma bought a house in the 1940s, you are much more likely to be wealthier, healthier, and better educated today.

Housing has an outsize impact on one's net worth. But that's only the first reason to be anxious about it.

Housing and Education

In the US, homeownership is also the key to better education for one's children. Housing districts determine access to schools. And many communities offer very limited options for renters. As a result, buying a house is one's ticket to the country's best public schools.

While America has a public education system, each school district relies heavily on local property taxes (as opposed to federal ones paid to and distributed from a central government). Districts that can sustain higher property taxes can finance better schools. As a result, public schools vary widely in terms of resources, quality, and curricula. An investment in a house is often an investment in the education of one's children.

Housing is intimately tied to access to quality education. This is the second reason people are anxious about it. There are others.

Housing and Retirement

Housing wealth is a key component of retirement income.

Sixty-five million US households are headed by someone older than 50. Close to 80% of these households own a home. Tens of millions of houses are owned by people who are — or will soon be — retired.

America does not have a robust safety net for retirees. Those who plan to rely solely on Social Security benefits are destined to live in poverty — with an average payment of less than $1500/month, which is less than a third of the average US salary. Even those who have an additional pension are not in great shape. Public retirement systems have a shortfall of $1 trillion in unfunded liabilities, meaning they have less money than they promised they'll have at this point.

Most Americans do not have enough saved for retirements. Instead, their net worth is tied up in their homes. In other words, their home is their retirement plan. This is the third reason people are so anxious about the value of their homes.

Housing and Healthcare

The lack of a robust safety net is a source of anxiety for younger homeowners as well. A 2019 study estimated that 530,000 families file for bankruptcy each year due to medical issues and bills. According to the study between 2013 and 2016, two-thirds of all personal bankruptcies were tied to medical issues.

The threat of medical bankruptcy is not limited to America's poor. It is more common among middle-class Americans to face "surprise" payments under the current system. Private health care is tied to one's job, so once you lose the ability to work, you often lose access to premium insurance.

As a result, one's savings are a necessary buffer in case of a medical emergency. And a big chunk of middle-class savings is tied into housing. So housing is not just a key to one's access to education and one's ability to retire with dignity; it is also an extension of one's health insurance.

Building on Bigotry

No wonder housing is a source of great anxiety. Trump was trying to tap into this anxiety in his tweet. It might prove to be effective.

The American middle class is stuck in a system that forces it to react aggressively to any proposed change to the status quo. The introduction of new kinds of people or new kinds of housing typologies is a threat to the value of middle-class homes, which, in turn, is a threat to the ability of tens of millions of households to build wealth, provide their children with quality education, retire with dignity, and survive unplanned medical emergencies. This is true in the suburbs, and it is also true in denser areas within large cities such as New York and San Francisco.

Whether or not the threat is real or imagined does not matter. Most people don't want to participate in an experiment. Resisting change always seems like the safest choice. It's easy to think of real estate as a zero-sum game — if someone else gains access, I must be losing something.

I choose to believe that people are good. Or at least not actively evil. We all have misconceptions and biases, but most of us do not wish to harm others or to prevent them from reaching their full potential.

I also believe that people respond to incentives. The American housing market incentivizes people to act like bigots, particularly when placed in the broader context of education, healthcare, and retirement planning. The system, as currently constructed, puts pressure on good people to behave badly towards others. Ultimately, this leads to outcomes that are bad for society as a whole.

While this is an American problem, it rhymes with similar issues in other countries and offers lessons that can be applied anywhere.

Technology and innovation have the potential to realign incentives towards better outcomes. But they also enable an even darker future.

Technology's Promise and Threat

A variety of innovations are undermining the incentives for bigotry. It is becoming easier for individuals to spread their savings across multiple asset types and strategies. Apps Robinhood and Wealthfront bring stock and bond investment to new audiences. Platforms like Angellist and Fundrise enable upper-middle-class investors to invest in venture capital and commercial real estate deals. Companies such as Point enable homeowners to convert a fraction of their home into cash quickly. Each of these innovations carries its own risks, but they do make it easier to people to diversify their savings and park less of their net worth in a single house.

Farther afield, innovations are promising (or threatening) to break the link between location and education. Children can access the world's best learning material on sites and apps from Khan Academy, Duolingo, and DragonBox. Companies like Primer, Outschool, and Cypher connect students with teachers and seek to empower parents who choose to homeschool their children.

Homeschooling has been growing steadily over the past few years. It does not refer exclusively to parents staying at home with their kids. Pooling resources can facilitate it among neighbors and local study pods.

Covid-19 drove hundreds of millions of families to experiment with some form of homeschooling. Most of them can't wait to send their kids back to school. But a significant minority might be willing to continue to explore this path even once the virus subsides. So far, homeschooling has not proven to be a practical solution for lower-income families. But anything that breaks the current housing-education complex is worth watching.

Changes in the jobs market will have a ripple effect on the school system. The rise of remote work will expand the housing options available for families and undermine the monopoly of specific cities and neighborhoods. This does not mean that everyone will move to the countryside, but it does mean that consumers will have more choice and that real estate, overall, will become more competitive.

More broadly, the growth of the Passion Economy — people's ability to earn a living by working on things they love outside of traditional corporate structures — will make it easier for more middle-class people to live anywhere. More importantly, it would make it harder for more middle-class people to qualify for a mortgage. Lenders don't like people who don't have a steady corporate job. The unholy alliance between middle-class housing, middle-class schools, and middle-class mortgages will be weakened. What replaces it might not be better, but it will be different.

Innovations in telemedicine, mixed reality, and transportation will contribute their share to altering the suburban landscape. Perhaps the most exciting innovations will be in the social and cultural sphere. People who are released from the old system's incentives could create their own communities based on a new set of values and trade-offs.

That last point is the most significant promise and the biggest threat. Given the freedom to choose, people might gravitate towards communities that are even more exclusive and less diverse. How will this play out? I will keep you posted.

Dror Poleg Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.