The Office Ratchet Fallacy

The New York Times has a new piece about differences in office occupancy between large and small cities. Emma Goldberg writes:

"The competition for parking space is getting steeper. Commutes are inching longer. Workplace lounges are filling up with commotion as junior associates play cornhole. What return-to-office debate? In some parts of the country, it’s been settled."

Settled, you say? The article tells the story of a fully occupied, prime office building in Columbus, Ohio; of a few law firms; and of a 27-person start in Miami whose employees sometimes work in person "even six days a week."

Beyond the anecdotes, it highlights a true difference between what it frames as America's "midsize and small cities" and giants like New York City and the San Francisco Bay Area. The author cites data compiled by Stanford's Steven Davis, Nick Bloom, and Jose Maria Barrero."

"In small cities — those with populations under 300,000 — the share of paid, full days worked from home dropped to 27 percent this spring from around 42 percent in October 2020. In the 10 largest U.S. cities, days worked from home shifted to roughly 38 percent from 50 percent in that same period..."

Superficially, a couple of things pop up from the data:

- In all cities, fewer people are working remotely today than a year ago.

- In smaller cities, the drop in remote work is indeed more dramatic.

The article attributes the difference to shorter commutes in smaller cities. Commutes definitely matter (as I Tweeted, "It's not the office, it's the commute."). But ultimately, city size seems to be a proxy for economic competitiveness more than anything else. This means that fewer people work remotely in smaller cities because these cities have economies that are less productive, less competitive, and less dependent on top-end talent and on the hyper-specialized matching of such talent to specific tasks.

Most small cities in the U.S. don't have the labor composition of San Francisco or Manhattan. And the small cities that do — Sunnyvale and Mountain View, for example — probably have very high remote work rates and low office occupancy rates.

The article is also too focused on the relative change in remote work over the past year instead of the absolute change of remote work over the past decade. According to the data cited, 27% of workdays are completed remotely, even in smaller cities. This figure is lower than it was a year ago, but it is pretty high and much higher than a decade ago.

The mayors of those "small" cities sure seem worried by these figures. The bulk of the article tells the story of a single, full office building in Columbus, Ohio. Projections published by the Ohio Mayors Alliance in 2021 predict that remote work "will affect between 24% of the workforce in Strongsville to as much as 39% of the workforce in Columbus, with an average impact of 33%" and "will have significant impacts on municipal income tax." So, the number cited as good news by the Times is considered bad news by the people who run those cities. (Also, note that Columbus has a population of more than 2 million people, so it's not clear why it was chosen as the prime example in an article that analyzes remote work in cities with 300,000 or fewer participants; Miami, the other main example in the article, has between 400,000 and 6 million people, depending on where you draw the boundary).

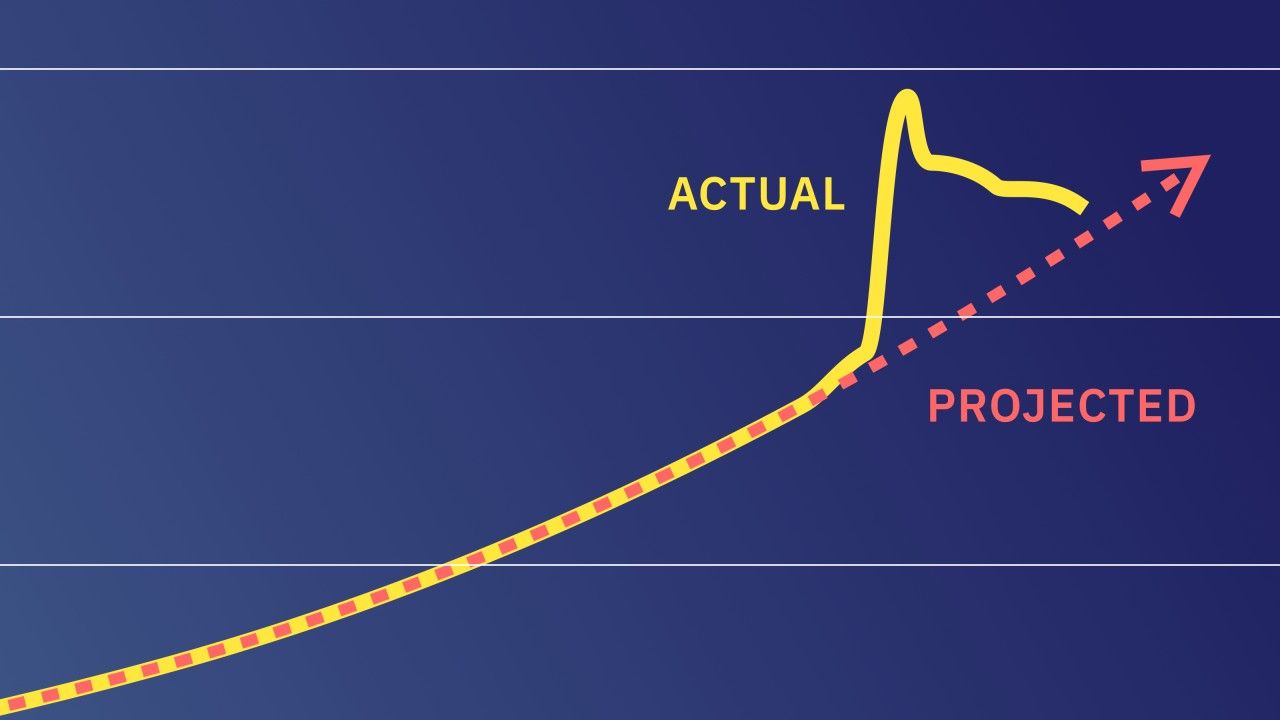

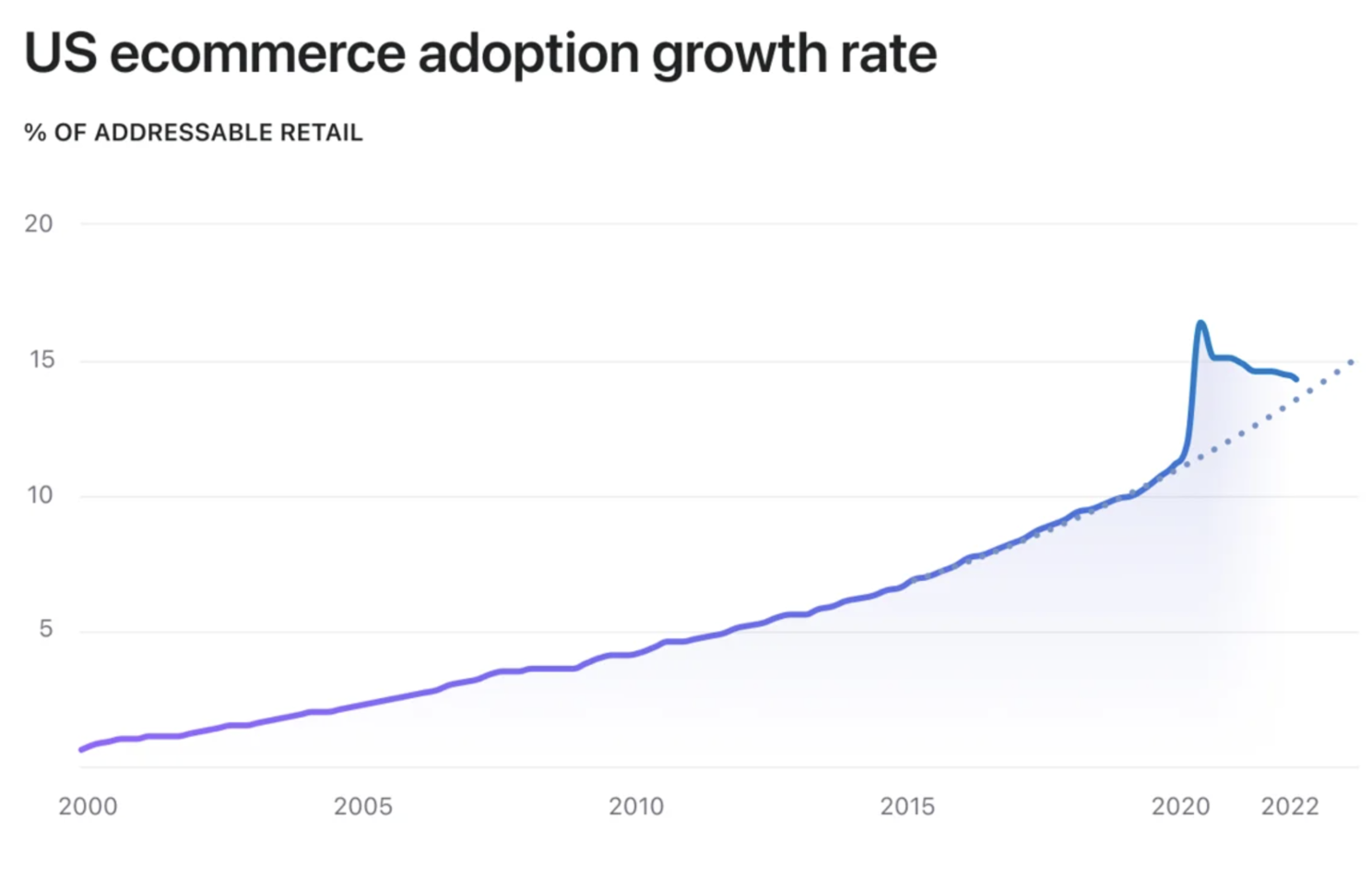

In any case, my point is that while fewer people are working remotely now that Covid restrictions have been lifted, the overall trend remains: The share of remote work will continue to rise. The retail market offers a great analogy to what's currently happening in the office world. Below is a remarkable chart from Shopify's recent layoff announcement.

Shopify overestimated the lasting impact of the pandemic and, as a result, expanded its headcount too quickly. Ecommerce's share of all commerce shot up during the pandemic but has since converged back to its overall long-term growth trend. Should we conclude from this that offline commerce has nothing to worry about? Of course not. Likewise, seeing a dip in remote work is not good news for landlords and traditional employers; it simply means they have a bit more time to adapt (and, for some, more ammunition to feed their denial).

But retail offers even more lessons. Benedict Evans points out that comparing e-commerce to all retail sales can be misleading. Offline sales include things gas stations that will never shift online and have become much more affected by inflation. As a result, relatively more money is spent on gas (offline) and, in turn, relatively less money is spent online. But in absolute terms, e-commerce spending remains well above where the original trend line predicted it would be in 2022. (Evans provides multiple charts and explanations, do check them out).

There's an overwhelming desire to wish remote work away. Landlords, employers, and mayors want things to return to "normal." And journalists love a good comeback narrative — the office is back! The debate is settled! Unfortunately, "normal" is not something we'll see anytime soon.

Dror Poleg Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.