The Office Won't Budge

Real estate is still a zero-sum game. But only for landlords.

Now Showing

Remember cinemas? Global ticket sales reached $42.5 billion in 2019. The highest-grossing film, Avengers: Endgame, brought in around $850 million. The lowest-grossing film brought in $220.

The success of films and many other consumer products follow a power-law distribution. Meaning that best-selling products — the hits — sell much much more than the average ones. And the amount of sales declines sharply as you move down the bestseller list.

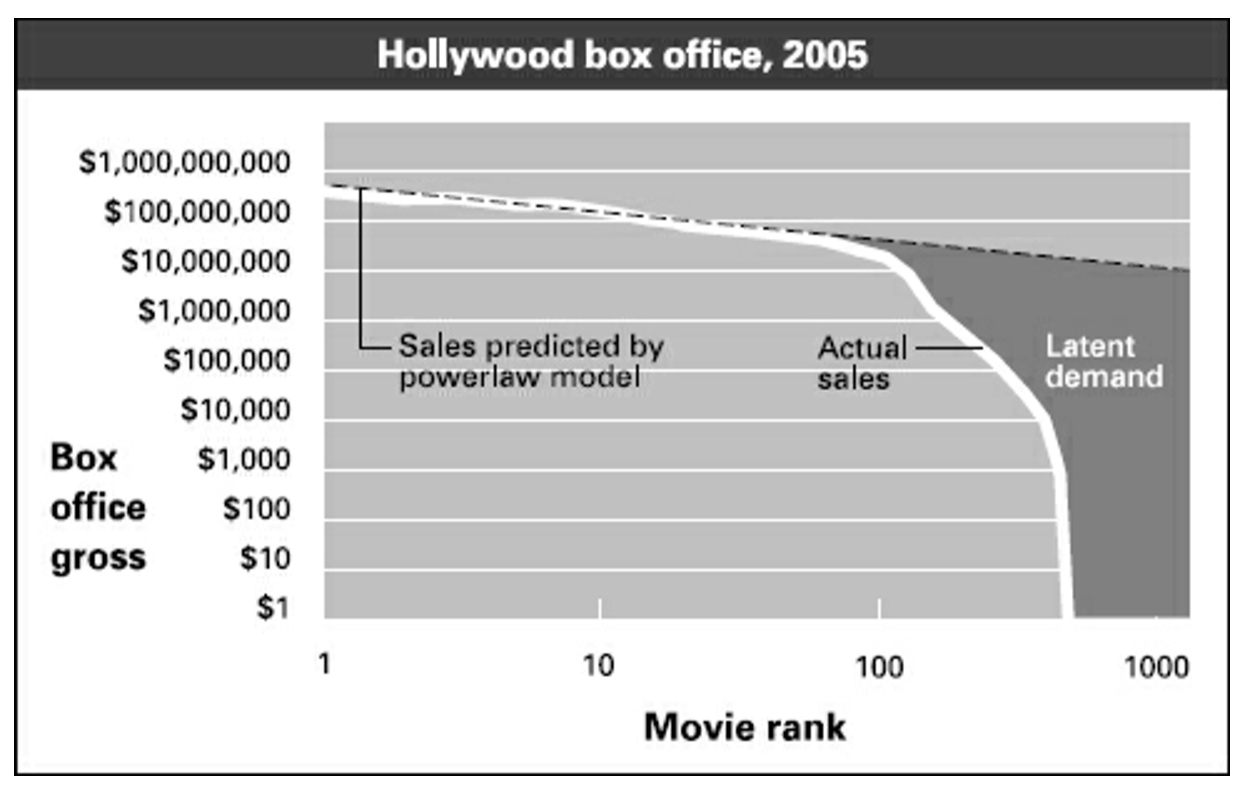

At least that's the theory. In practice, the distribution of movie sales follows a more extreme, and less orderly pattern. Below is a chart of box office sales from 2005, compiled by Chris Anderson. The dotted line represents projected sales based on a power-law distribution.

Every year, around 2,600 films are produced around the world. As you can see, for the first 100 films or so, actual sales proceed according to the model. But they then start to drop dramatically and reach zero around the 600th film. How come?

As Anderson explains in The Long Tail, the reason is real estate. The world has a finite number of cinemas with a finite number of seats. This scarcity forces cinema operators to allocate their screens to the films that are most likely to sell well. Other films don't even get a chance to sell tickets — not because no one wants to watch them, but because no one wants to show them.

The films that don't make it to the cinema go directly to streaming services. As a result, streaming services can capitalize on latent demand for films. This demand is represented by the dark area in the chart above.

Streaming did not kill traditional media companies. It gave them a new way to monetize their films, especially older ones. Disney, for example, is ploughing plenty of old material into its new streaming service. Netflix, HBO, and Amazon Prime also feature plenty of classic films and international titles that can no longer make it to the cinema.

Some of these films end up being watched by millions of people every year. When more films can be watched, more films are watched. The internet-enabled (and forced) media companies to transcend the laws of scarcity and adapt to a world of abundant choice. But the internet didn't stop there.

An Unstoppable Force

As we discussed last week, the rules of the online world are increasingly applicable to the offline world. The fact that people can work and access services and experiences from anywhere creates an abundance of choices that will alter the distribution of human communities within and between cities.

Latent demand for office space can now be unlocked. Because people are no longer forced to go to a large office in the center of the city, they can suddenly choose to go to a satellite office closer to home, or to a coffee shop, or to a working retreat, or to spend more time at home, or to visit a coworking space, or to take advantage of on-demand meeting rooms.

If the world of films and music is any indication, more options will mean more demand. The ability to work from anywhere can offset the decrease in demand for traditional offices somewhere. Overall demand for places to work in might actually go up.

But it's still bad news for most landlords.

An Immovable Object

It doesn't take a Nobel laureate to understand the difference between media assets and real estate assets. But here's a quote from Prof. Robert J. Shiller, just in case:

"You can ask someone to move a building out of Manhattan, but you won't find it feasible"

Shiller was commenting on the future of apartment buildings, but the point is equally valid for offices.

There's the rub. If someone can't watch Casablanca or The Godfather in the cinema, the owner of the film can still "deliver" it to wherever the customer is. But if someone can't — or doesn't want to — go to his office in midtown Manhattan, the owners of the Empire State Building or Hudson Yards can't "deliver" the office to them. That person might still go to a building, but that building is likely owned by somebody else.

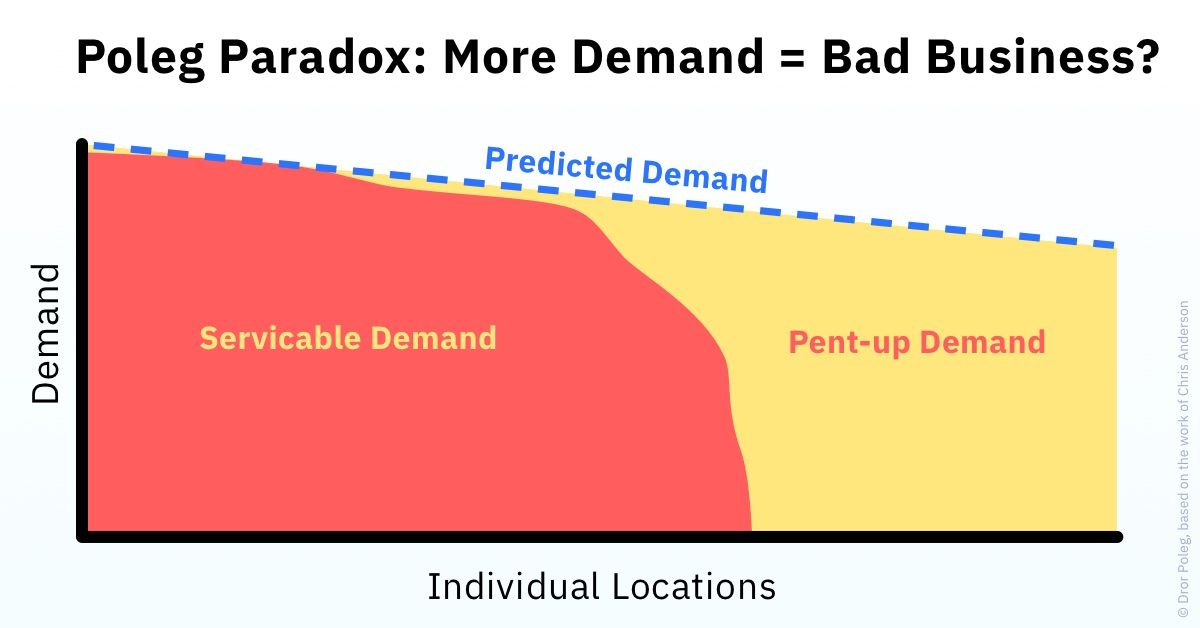

The landlords still have a monopoly. But demand is growing outside of the monopoly board. And since buildings can't move, those who own them are at a disadvantage. I call this the Poleg Paradox: A situation in which higher demand is bad news for incumbents. It can be observed when one party to the zero-sum game can suddenly play by different rules.

Of course, landlords are not helpless. They can still convince customers to come back to the board — or expand to new areas. How? That's a whole different story.

Dror Poleg Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.