Welcome To The Jobless Boom

Two years ago, I pitched a piece to The Atlantic called "AI Is Blurring the Boundaries Between Booms and Busts." The argument was that the familiar cycle — growth leads to hiring, hiring fills offices, offices fund cities — was breaking down. Not temporarily. Structurally.

San Francisco was my case study. The city was supposedly staging a comeback. AI companies were flooding in, investors were pouring billions into startups, and Nvidia was on its way to becoming the most valuable company in the S&P 500. Marc Benioff tweeted that AI companies were "looking for huge amounts of space." The Economist declared that San Francisco had staged "a surprising comeback." But the city wasn't booming or busting. It was doing both at the same time. And that wasn't a paradox to be resolved. It was a signal.

Here's what I wrote in my original pitch:

We may be witnessing a permanent shift in the relationship between economic inputs and outputs — between the amount of land and the number of people required to produce a given amount of revenue and profits.

I pointed out that OpenAI needed fewer than 700 employees to generate its first $1 billion in revenue. Anthropic employed even fewer people and was approaching similar levels. Google, by comparison, needed around 2,500 people to reach the same milestone twenty years earlier. Big Tech companies were laying off tens of thousands of employees while growing their revenue. The number of people employed as software engineers had peaked in 2019.

I argued that expecting AI to revive central office districts was like expecting automation to revive factory towns. That our cities were built for a world that no longer existed — one in which economic growth meant more people showing up to more offices. And that the decoupling of economic output from physical inputs was not a temporary post-COVID hangover but a structural break. San Francisco was my main example, but the argument was never about one city. As I wrote in my original draft: "San Francisco is a microcosm of America at large."

The piece that ultimately ran in The Atlantic in July 2024 kept much of the diagnosis. It documented the broken correlation between macroeconomic indicators and office demand. It cited the NAIOP model that had reliably predicted office demand for decades but was suddenly off by 90%. It quoted economists grappling with the divergence.

But the sharper edges were filed down. The original draft argued that cities needed to become "as flexible and amorphous as the economic activity they contain." It proposed that cities treat innovation profits the way Norway treats oil revenue — taxing them highly but allocating revenue to an independent fund, insulated from the current government, that invests for the long term. It called for radical liberalization of zoning, planning, and employment licensing. The published version ended with more conventional prescriptions: diversify the economic base, streamline construction, make cities more attractive.

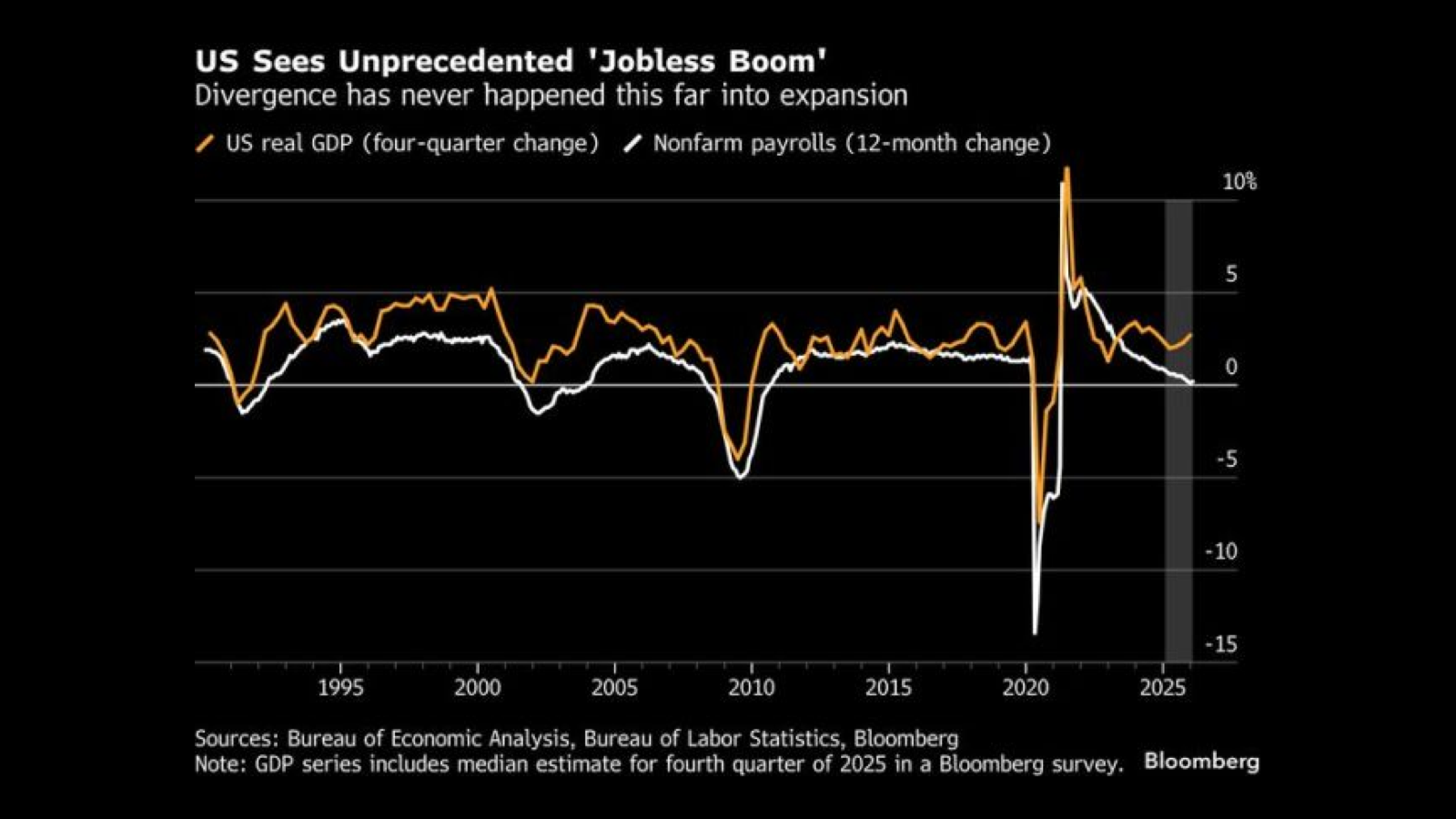

Since 2024, the dynamic I identified has only intensified. Today, Bloomberg published a piece titled "Unprecedented 'Jobless Boom' Tests Limits of US GDP Expansion." The economy grew 2.7% in 2025. Employment barely grew at all. The accompanying chart shows US real GDP and nonfarm payrolls — two lines that moved in near-lockstep for over three decades — diverging in a way that, according to Bloomberg, "has never happened this far into expansion."

This is what it looks like at the macro level when the relationship between economic inputs and outputs breaks.

Bloomberg compares the current moment to the "jobless recovery" of the early 2000s. That framing implies a lag — a recovery that will eventually catch up. But consider the data. In 2004, Google needed 2,500 employees to produce $1 billion in annual revenue. Today, Anthropic has 2,500 employees and a revenue run rate of $14 billion. Same headcount. Fourteen times the output. Two decades apart.

That is not a lag. That is a new relationship between people and economic output. And it has implications far beyond office vacancy rates.

The economy no longer needs the same number of people, the same number of desks, or the same amount of space to produce a given amount of wealth. GDP can grow while payrolls flatline — not because something is broken, but because the production function itself has changed. The Bloomberg chart is not showing an anomaly. It is showing the new normal.

Two years ago, I saw this playing out at the city level — in the gap between San Francisco's booming AI sector and its record-high office vacancy. Now it's visible at the national level. The lines on the chart are not going to reconverge. Not through the old mechanisms, at least.

The political system is already responding. Since my piece ran, San Francisco elected a new mayor who has embraced many of the reforms I proposed — liberalizing zoning, streamlining conversions, making the city more adaptable. And New York elected a populist socialist mayor, in no small part because New Yorkers experienced the divergence firsthand: the economy was growing, the stock market was soaring, and yet their material lives weren't getting better. One city chose to adapt to the new reality. The other chose to redistribute within the old one. Both responses confirm that the structural break is real and that people can feel it, even when the GDP numbers look fine.

The question is no longer whether the relationship between economic growth and employment has changed. It's what we're going to do about it.

My original draft had a section on that, too — one that didn't make it to print. I argued that cities need to become as flexible and amorphous as the economic activity they contain: liberalize zoning to mix residential and commercial uses, streamline conversions from one use to another, make housing dramatically easier to build, loosen employment and licensing rules to let new professions emerge. On the fiscal side, I proposed that cities treat profits from innovation the way Norway treats profits from oil — tax them meaningfully, but allocate a significant share to an independent fund that invests for the long term, maintains reserves, and funds education, healthcare, and infrastructure outside the reach of the current government. That way, the windfall from a jobless boom actually reaches the people the boom left behind.

Two years later, those ideas feel less radical and more urgent.

Best,

🎤 How will AI reshape our cities, companies, and careers? My speaking schedule for the year is filling up. Visit my speaker profile and get in touch to learn more.

Click here to book a keynote or learn more.

Old/New by Dror Poleg Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.