Keeping NYC On Top

In early 2021, I was asked by Scott Rechler and RXR to write down my views on New York City's future. These included my predictions about the impact of remote work, the validity of existing economic theories, and what the city must do to become more attractive.

I wrote the paper for internal use, but Scott has kindly allowed me to share it with my subscribers. It was written 18 months ago, but its recommendations are more relevant than ever.

New York City's offices are still around 50% of their pre-Covid capacity. The city is struggling with a massive budget shortfall in property and business taxes. Public transport ridership is more than 30% below pre-Covid levels. At the same time, crime is up, and housing and other goods and services are significantly costlier.

President Biden declared Covid-19 "over," and the US economy regained the jobs it lost during the pandemic. But New York City is still 162,000 jobs short.

Below are my thoughts on why New York got to this point and what the city can do to get better.

___

New York City always comes back. But it doesn’t always come back quickly, and it never comes back the same. Post- COVID, the city has an opportunity to come back better than ever. It’s an opportunity it can’t afford to miss.

The good news is that COVID is not a long-term threat to the city. Once the virus is under control, a wave of pent-up demand for in-person activities will be unleashed. The opportunity to work, socialize, travel, and even shop in dense urban environments will be as appealing as ever. Unlike 9/11 or the collapse of Lehman Brothers, and the financial meltdown that followed, New York is just one of COVID’s many victims. If anything, COVID merely intensified trends that were already clear five or more years ago.

The bad news is that COVID forced a rethinking of individual and corporate priorities. People have more choice than ever on where and how to work, socialize, travel, and shop. They are now fully aware of their options and no longer bound by old habits or inertia. Unlike in previous crises, New York City’s specific predicaments receive no particular sympathy from the world, the Federal Government, business leaders, or even NYC’s own residents. And even before COVID, the city has already shown a reluctance or inability to take bold action in the face of troubling trends.

The best news is that physical locations are becoming consumer products — places that individual people choose to spend time in, even though they can be anywhere else. This choice applies to specific buildings, individual neighborhoods, and whole cities and states.

People always had a choice, but the intensity of competition between locations and the focus on individuals rather than corporations makes it a whole new game. It’s a game that New York City is favored to ultimately win. But the city cannot afford to spend two decades figuring out a new game plan. To stay on top, it has to take bold initiatives now.

In the following pages, we explore (1) the consensus view on the economic and cultural role of cities, (2) why the coming era of choice is different from anything we’ve seen before, and to what extent it reflects a departure from the consensus; (3) why New York City has the potential to prosper in such an era and what it can do to fulfill this potential.

REMOTE VS. CITIES

In 2001, Frances Cairncross predicted how The Death of Distance would reshape cities: “As individuals spend less time in the office and more time working from home or on the road, cities will change from concentrations of office employment to centers of entertainment and culture.”

Over the two decades that followed, Cairncross turned out to be 50% correct. Work did become somewhat more flexible, and cities did become more entertaining. But the dominance of well-located downtown office buildings only increased.

Between 2004 and 2015, companies in growth industries started showing a strong preference for urban areas. Startups took an “urban turn,” with more of them choosing to locate in New York, Boston, Santa Monica, and San Francisco proper rather than in the sprawling Bay Area, Route 128, or the suburbs of large cities. U.S. job growth “disproportionately favored” dense metro areas.

The Great Financial Crisis was a mere bump in NYC’s upwards trajectory. By 2012, the city recovered all the jobs it lost in 2008-2009. During the same period, the U.S. as a whole recovered a mere 40% of lost jobs. By 2016, “nearly all of America’s job recovery has been in the nation’s largest urban areas.”

Instead of making density less critical for economic activity, the falling cost of communication and transportation had the opposite effect. As Harvard Economist Edward Glaeser pointed out in 2007, “a central paradox of our time is that in cities, industrial agglomerations remain remarkably vital, despite ever easier movement of goods and knowledge across space.”

The rise of knowledge work explains this apparent paradox. Fewer people are now employed in manufacturing. Machines have become pretty good at producing things, but humans are still better at producing knowledge. That means coming up with new products, designing them, telling stories about them, listening to feedback from customers, and collaborating with other humans to create even better products.

Knowledge work is less structured, more spontaneous, and harder to teach. “Our knowledge,” says Glaeser, “builds on things that we learn from people around us.“ Being close to other knowledge workers makes it easier for us to learn new things and develop new ideas. As such, knowledge work is best done in cities.

Data from the past few decades corroborates this theory. As Professors Gilles Duranton and Diego Puga explain, “urban density boosts productivity and innovation, improves access to goods and services, reduces typical travel distances, encourages energy-efficient construction and transport, and facilitates sharing scarce amenities.”

Urban agglomerations allow companies to access a large pool of highly-educated professionals. But more importantly, a large pool allows for more optimal matching of individual candidates to specific jobs. This is a subtle but critical difference and a key to understanding where offices and cities are headed.

Consider the story of Mark Zuckerberg. The student- entrepreneur founded Facebook in Cambridge, MA, a town with perhaps the highest concentration of highly- educated people on earth. Staying put, Zuckerberg could have hired thousands of software engineers, designers, and managers of a general quality that is second to none.

But instead, as Enrico Moretti points out in The New Geography of Jobs, Zuckerberg chose to move to Silicon Valley to grow his new business. In the Valley, the talent pool is bigger, and Zuckerberg could find engineers that were excellent and specialized in the exact type of processes, technologies, and products he was looking to deploy.

Moretti compares this dynamic to an online dating site. Would you rather date in a pool of 100 candidates or 10,000? A bigger pool makes it more likely that you’ll find Mr. or Mrs. Right. And just as with dating, “right” is a subjective standard — the optimal outcome is not about matching the two best people; it’s about matching two people that fit each other best.

In a larger pool, it’s more likely for a higher percentage of candidates to find an ideal match. A larger pool creates more value for everyone: companies make more money when they can hire ideal employees, and ideal employees get paid better when they match with a company that needs their specific skills.

In creative industries, the ideal candidate is not just marginally better. As Google’s Vice President of Engineering told the Wall Street Journal, one top-notch engineer is worth “300 times or more than the average.” The company would rather “lose an entire incoming class of engineering graduates than one exceptional technologist. Many Google services, such as Gmail and Google News, were started by a single person.”

In the best cities — New York in particular — the talent pool is not only deep, but it also spans a diversity of industries and ecosystems. This creates unique opportunities for cross-pollination between sectors such as tech, finance, media, real estate, retail, healthcare, government, and professional services. As the economist Matt Clancy points out, high population density engenders more patents that combine technologies and ideas from different fields. A diverse talent pool like New York’s also enables companies to grow in place even though their business evolves to depend on different types of employees, partners, and clients.

Cities are not just better at matching candidates and jobs; they are also more fun and inspiring. As Glaeser pointed out, urban residents are more likely to go to a concert, visit a museum, go to the cinema, or drink at a bar than people with the same income and education levels in non-urban areas. Cultural activities that “feature live interactions instead of passive TV watching” have “a particular appeal to wealthier and more educated people.”

While the economic argument explained why cities grew during the 20th Century, the cultural argument homed in on what made them particularly attractive during the early years of the 21st Century: Companies are increasingly reliant on a new “Creative Class” made of people who “draw principally upon their knowledge or mental labor to engage in research, innovation, and product design and development, or to manage people, or engage in artistic and cultural production.”

As Richard Florida explained, members of the Creative Class prefer to live and work in cities. Even if they could be equally productive in a suburban office park, the fact that they wanted to live in big cities meant that companies had to follow them there. The economic and cultural benefits of agglomeration led to what Florida called “winner-take-all urbanism,” benefitting a small number of large cities and leaving all others behind.

Both Glaeser and Florida acknowledged that a lot of innovation was also being produced outside of dense cities. Silicon Valley, for example, is a long strip of low-density towns. Such areas were described as “urban agglomerations” rather than “suburbs,” despite their low density and dependence on highways.

Both Glaeser and Florida also acknowledged that cities would have to evolve in order to remain affordable and safe. But overall, the consensus was that the information revolution would not reverse urbanization in the developing world; instead, it was expected to revive and intensify it.

The urban trajectory for the 21st Century seemed clear. And then it started to crack.

AGGLOMERATION OVER URBANIZATION

Even before the pandemic, a new paradox was taking shape: the economy was growing, but the most prosperous cities were not. In 2018, U.S. GDP increased by nearly 3%, but net migration to New York City, Los Angeles, and San Francisco was negative. Globally, Creative Class magnets such as London and Paris were experiencing similar declines. Winner- take-all-urbanism was starting to reverse.

How to explain this? Like a man with a hammer, urbanists and real estate professionals turned to the old familiar nails: to handle the upsurge in demand, cities need to build more housing, invest in new infrastructure, and reform the land-use and tax policies. All of which is true.

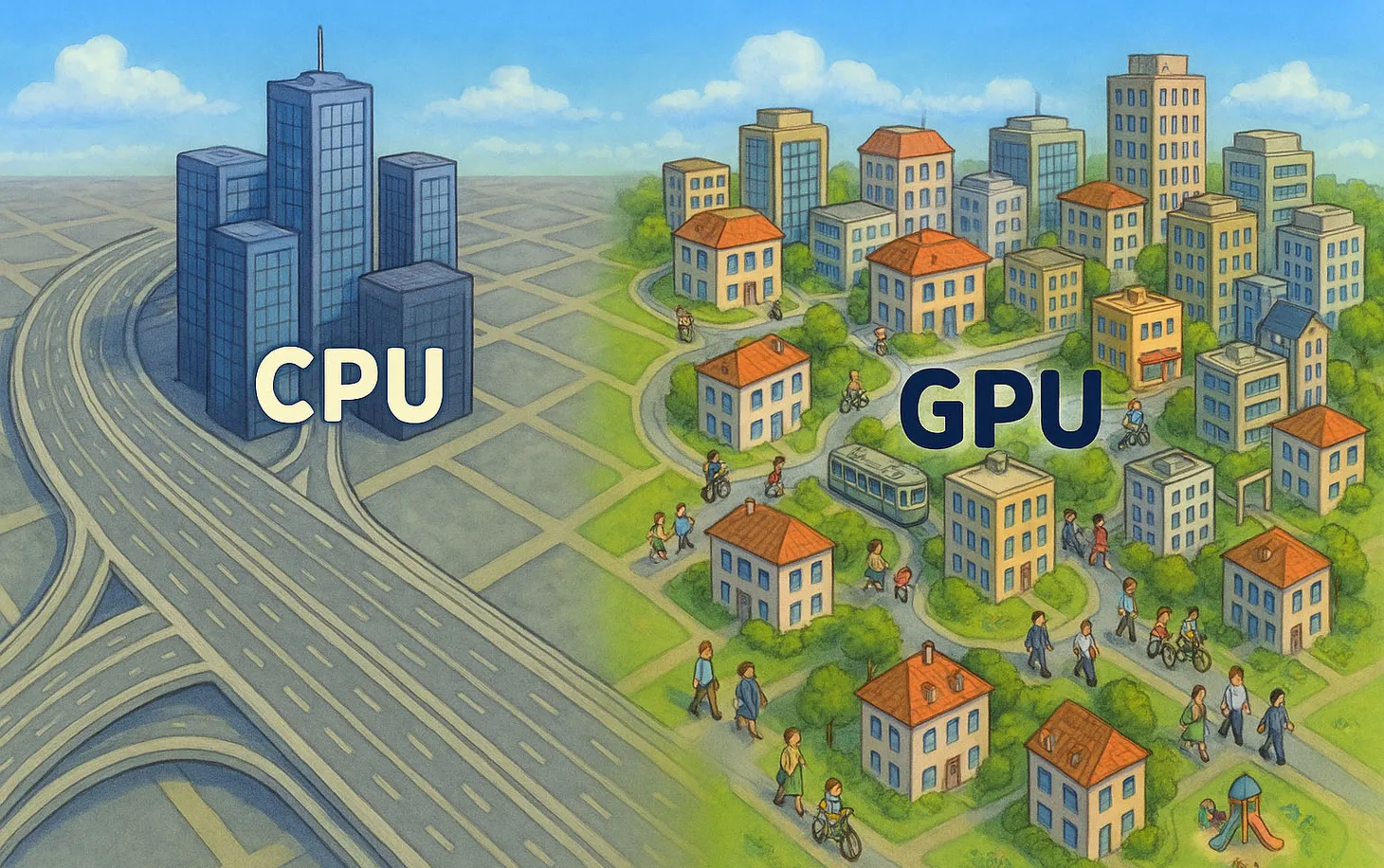

But focusing on old truths obscured a significant change in the nature of agglomeration itself: For the fastest-growing companies, being able to tap into talent anywhere became more important than having all their people in one place.

In the middle of the 2010s, Amazon, Facebook, Google, Apple, and others started splitting their headquarters into multiple locations. These locations are not “regional HQs” or “local branches”; they are a base for employees that contribute to the development of key products and services, as well as for some of the company’s key executives.

Stripe, one of the world’s most valuable start-ups, went a step further. In 2019, it “opened” a new hub that was fully remote — it consisted of people that, by definition, were not expected to show up in any particular place. According to Stripe’s CTO, the purpose of this new approach was to “tap the 99.74 percent of talented engineers living outside the metro areas of our first four hubs” in San Francisco, Seattle, Dublin, and Singapore.

Companies that relied on deep urban talent pools were suddenly content to hire in smaller cities and non-urban locations. Did agglomeration no longer matter? Quite the opposite: Agglomeration became too important to be left to a single city. A larger talent pool enables better matching with specialized talent, and the internet is the largest talent pool of all. This does not mean that it’s no longer ideal to have all your team in one place, but it does mean that the cost of not being together can be offset by the benefits of accessing a larger talent pool.

Until very recently, it was not possible to have a truly distributed team. Online collaboration was inefficient, and the productivity cost outweighed the benefit of accessing a bigger talent pool. During the 2010s, both sides of the cost-benefit equation changed: communication technology reached a critical level of maturity, and access to specialized talent became more important than ever. These changes encouraged and enabled more companies to split their core teams into multiple locations.

Observing this dynamic in 2019, I posed a simple question in my book about the future of real estate: “If employees can collaborate across offices, why do they need to be in the office at all?”

And then the world sneezed. COVID-19 forced the largest office occupiers to go fully remote. This move was temporary, and it was uncomfortable for many. But it showed that traditional office space was less critical for a variety of activities and tasks than previously believed. And by extension, it showed that some of the highest-paying jobs could be performed away from the most expensive cities.

Within months, many of the world’s largest employers announced plans to adopt some level of remote work on a permanent basis for the majority of their employees. These companies will continue to tweak their plans. A more extended absence might make employees and employers miss the office, but it also allows them to acquire new habits, adopt new tools, and make life decisions that are difficult to reverse.

How many of them will choose to return to the office — and the city? Nobody knows. But the question itself tells us we’re entering a new era of choice. One thing is certain: The old normal is not coming back. This is not 9/11 or The Great Financial Crisis.

9/11 was a severe blow to the city, but it did not expose or expedite any significant changes to how people work or communicate. The companies that could not return to their offices struggled, and there was no doubt they would return to normal operations as soon as they could. The technologies that enable remote or distributed teams were simply not yet available. In 2001, long-distance calls were considered a luxury. The number of fixed phone lines on earth was less than 15% of the current number of mobile phones. And less than 2% of retail sales were conducted online.

In 2008, the best-selling phone in America was made by Motorola, and the Top 10 list included two models from Nokia. Less than 12% of mobile phones had broadband internet, and those that did had 3G, which was about ten times slower than the 4G networks we use today. Uber, Instagram, Slack, Zoom, and Google Docs were not yet invented, let alone stable and easy to use.

This time is different. The old economic models and theories are based on a world governed by scarcity, a world where working together meant being in the same place because that was the easiest, most efficient, and therefore most productive way for companies and their employees to work. There are many benefits to being in the same place (from culture-building to mentorship and real-time collaboration), but these benefits are not as overwhelming as they once were, and new tools will continue to undermine their importance — at least for the majority of office tasks.

The death of the Old Normal is not bad news for New York City. At least, it doesn’t have to be. If more people could live and work anywhere, many of them would love to live in the world’s greatest city. But to remain great, New York will have to shake off the assumption that the best people must be here and make itself attractive and delightful in a variety of new ways.

CHOOSING NEW YORK CITY

As we enter the Spring of 2021, New York City is showing signs of life. But optimism should not lead to complacency. Hundreds of thousands of people have lost their job. Thousands of businesses have shut down. The residential real estate market is held together by an eviction moratorium, mortgage forbearance, and the fact that sellers and renters are keeping inventory off-market in hope of better days. The commercial market is held together by short-term renewals and inertia, with most companies delaying long-term decisions until the fog of Covid clears up. It is reasonable to expect things to improve in the second half of 2021, but employers and employees are still considering their next steps, and their return should not be taken for granted.

The summer sun will give New York an opportunity to shine. Warmer weather, rising vaccination rates, and pent-up demand for any type of human interaction (and any reason to get out of the house) will drive back many residents and many more domestic tourists. The summer sun should be used to showcase the city’s vision for the future — not in words but in actions.

Current and would-be New Yorkers want the city to succeed. To attract and retain them, New York will have to lean into its strengths and address its weaknesses. This was true pre-COVID, but now the stakes are higher, and it’s no longer possible to kick the can(s) down the road.

All the things that make NYC great need to improve.

The allocation and regulation of land use should be reoriented around the human experience. Streets need to become more walkable, cleaner, and safer. The Open Streets that sprang up during the pandemic should become permanent fixtures of the urban experience. A significant percentage of street parking should make way for wider sidewalks, bike lanes, proper trash collection stations, and other public uses. The city should be allowed and encouraged to adapt. Repurposing old buildings for new uses should be easier, and experimentation should be encouraged and incentivized.

The city’s vast infrastructure should be leveraged to enable more people to live with easy access to economic opportunities and urban conveniences. Increasing density along the city’s subway lines should be a priority. Public transportation networks should be better integrated with airports and regional air as well as with new forms of transportation, including ride-sharing and micromobility. Infrastructure should be reliable and kept in a state of good repair. Moving in and around New York City should be a delight — not something people “tolerate” on their way to more pleasant activities.

Environmental, social, and economic challenges should be addressed with creativity and boldness. The need to tackle big problems should not be a stick with which the government beats private businesses but an opportunity to leverage local talent, innovation, and financial resources to develop solutions from which the whole world can benefit.

New York-based companies already fund and develop PropTech and UrbanTech solutions that are used across the globe. It’s time to practice what we preach: The city should prioritize the development of these ecosystems and harness them to address every aspect of its operation.

To attract talent, the city should not ignore or downplay the challenges it faces. These challenges are an attraction in themselves. The best and brightest care about salaries and conveniences, but they are ultimately driven by a sense of purpose — by the opportunity to work on solutions that align with their values and make a real difference. Local universities and cultural institutions can help channel this energy toward its most productive uses.

Perhaps the biggest change should be one of attitude: From a sense of complacent superiority to a sense of aspirational excellence. Every interaction with the city should inspire locals and impress visitors: on the streets, in the subway, in schools, in government offices, and beyond. There are many excuses why this is not possible. But there is no real reason why New York should not be the best — an example of how cities can create economic opportunity, address social inequities, tackle environmental challenges, and rally a diverse citizenry around shared goals.

In 1948, E.B. White wrote that “No one should come to New York to live unless he is willing to be lucky.” In 2021, plenty of people are willing to bet on the city’s ability to come back better than ever and that it can do so now. New York should feel lucky enough to bet on itself by addressing its challenges head-on —boldly, decisively, now.

Dror Poleg Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.