Tragedy of the Uncommon

Lessons from AI and urban planning on why it pays to keep things open — and how exclusivity destroys value.

🎧 I chatted with Michael Marciano about the evolution of my own career, my analytical approach, the future of work and cities, and more. Listen on Spotify or Apple Podcasts.

🧠 The upcoming cohort of Practical AI is filling up. We'll dive into the latest tools and learn how to use them for marketing, financial analysis, and general business automation. The schedule would be particularly convenient for those in Asia-Pacific of central/western US. Learn more here.

I live ten minutes away from the beach on Long Island, New York—ten minutes on foot. You'd think I'd be on the beach every day. But the beaches near my house are private — restricted to specific homeowners or country-club members— so I am technically not allowed to enjoy them. And yet, the lack of access doesn't bother me; I don't want to go there anyway.

This is not a spiteful paraphrase of Groucho Marx's quip against clubs that would have me as a member. I meant it literally: the beaches are not attractive, even though they are exclusive. As a matter of fact, the beaches are not attractive because they are exclusive. This is a distinctly American phenomenon I shall call "the tragedy of the uncommon." The tragedy describes and explains many peculiar aspects of American cities and suburbs, and it can even guide our approach to Artificial Intelligence and open-source software.

You may have heard about the opposite economic concept, the tragedy of the commons. It refers to a situation where individuals acting in self-interest can ultimately deplete a shared limited resource, even when it is clear that it is not in anyone's long-term interest for this to happen. For example, uncoordinated fishermen can deplete a lake's fish population; each of them tries to maximize his returns, but ultimately everyone loses because there are no fish left. Alternatively, the fishermen can coordinate their work (or the government can limit fishing to specific times/quantities) to ensure the constant regeneration of the local fish population — and the long-term wealth of everyone involved.

In short, the tragedy of the commons describes situations where unrestricted use of a resource leads to its destruction and a sub-optimal economic outcome. This is a well-established concept in economics. But its opposite is less explored. The tragedy of the uncommon describes situations where the restricted use of a resource leads to its destruction and a sub-optimal outcome. This usually happens when a resource is in private hands.

Classical economics assumes that an owner would do whatever it takes to make the most out of a resource they own. But in reality, this doesn't always happen. We'll consider some reasons in a moment, but first, let's look at a specific example.

Last month, my mother-in-law joined my wife, kids, and me for a vacation in Israel. She's been there many times, but this time, she got to experience it as a local rather than a visitor. We stayed in a middle-class residential neighborhood not far from the beach. Israel has many faults, particularly its treatment of Palestinians and, more recently, of its own Jewish citizens. But three areas in which Israel excels are fun beaches, great food, and vibrant streets.

The country's short shoreline has more than 100 public beaches. My mother-in-law was constantly in awe at the fun atmosphere and good food at Israeli beaches and how integrated the beaches are with the rest of the urban fabric. The beaches in Israel are accessible to anyone, yet they are far more attractive than the exclusive beaches near my home on Long Island. How come?

Of course, there's the natural beauty of the Mediterranean and the wonderful ingredients of Middle Eastern cuisine. But the main reason Israel's beaches are much nicer is that they're public. Openness enables access to a larger pool of customers, which can sustain better amenities and restaurants, and justifies a deeper integration with private and public transportation systems. The abundance of public beaches also enables experimentation with different services and designs and an ongoing evolution: Once one beach introduces something that works (a new type of parasol or a popular dish), many others copy it. This is not an argument for socialism. Most public beaches still have private businesses (restaurants, parking operators, equipment rentals), so the general openness benefits the public and increases the wealth of private business owners. And yes, there are also a few — very few — private beaches. We'll get back to these in a moment.

But first, let's contrast the above with what happens on Long Island, New York. Long Island's shoreline is as long as Israel's, but it has about 50% to 70% fewer public beaches. Private beaches are the norm, in keeping with the American tradition. As a result, most of them cannot sustain any good restaurants with fresh ingredients, have limited or no services and amenities, and aren't conveniently integrated with public transport (or even basic walking paths, for that matter). The limited number of beaches and their lack of dynamism also limit their evolution and improvement. And to make things worse, this state of affairs also makes Long Island's public beaches worse than they could have been. Many public beaches are "truly" public, meaning they feel more like a government-run facility than a market-oriented business — they have limited and bad dining options and are all relatively uniform.

At this point, you may mumble to yourself, "Yeah, OK, but exclusivity is valuable in itself; the fact that the beaches are empty is a feature, not a bug!" This is true up to a point. And it is indeed the working assumption behind the current American system that exclusive is good and hence more exclusive is more valuable. It's easy to see why the public at large loses from this arrangement, but who cares about the public as long as the owners are happy with their property? That's where I disagree.

I contend that the current arrangement also harms those who own private beaches. This arrangement diminishes the value of the beaches or, at the least, limits them from reaching their full potential. As mentioned above, I live close to some of these private beaches, and I have no interest in spending time there. They're inconvenient to access, the food is sub-par compared to other local options, and hardly anything is happening.

If that is the case, why aren't the owners opening things up? Don't they want to make the most of their asset? They do. But they don't know any better. The assumption that exclusive = valuable is deeply ingrained. Once Americans (like my mother-in-law) visit another country, they can be astounded by the merit of an opposite approach. They wonder, "Why can't we have this back home?". But most people don't reach this realization, and, in any case, now that most beaches are private and locked into a particular business model (private membership or funding through "community" fees from a small number of adjacent houses), it would be tough for them to switch to a different model. That's why it's a tragedy: Everyone acts according to their best interest, but the outcome is that even the rich people on Long Island only get to go to pretty crappy beaches with lousy food and limited accessibility.

Of course, there is also room for some genuinely private beaches. Yes, extreme exclusivity is valuable to some people. But the balance between public and private access should probably be the inverse of what it is now — the default should be public. This would enhance the welfare of the whole public and, on the net, increase the total value of private beaches and beach-related private businesses.

The same dynamic can be observed elsewhere. Many of America's wealthiest neighborhoods don't have sidewalks. Here too, a narrow view of "exclusivity" and "profit" is to blame. Historically, the lack of sidewalks was seen as a way to discourage or prevent "unwanted" people from stumbling into the neighborhood. And since sidewalks are costly to build and maintain, many communities chose not to build them in order to "enhance" the value of houses and extend private yards all the way to the actual road. The end result is yet another tragedy of the uncommon: the actual residents suffer from being unable to walk anywhere. This makes them less healthy, more lonely, and more dependent on expensive cars and gasoline. It also limits integration with public transport and the development of local amenities such as restaurants, clinics, and other services. By restricting the use of land, its owners become worse off financially, physically, and socially.

Many people are stuck in a kind of Architectural Stockholm Syndrome. They assume that the environment they grew up in is optimal, and they develop attitudes and theories to justify it — despite clear evidence that it harms them. Only when they get to live in another environment, do they realize that a better way is possible. And even then, they often assume that it's only possible elsewhere.

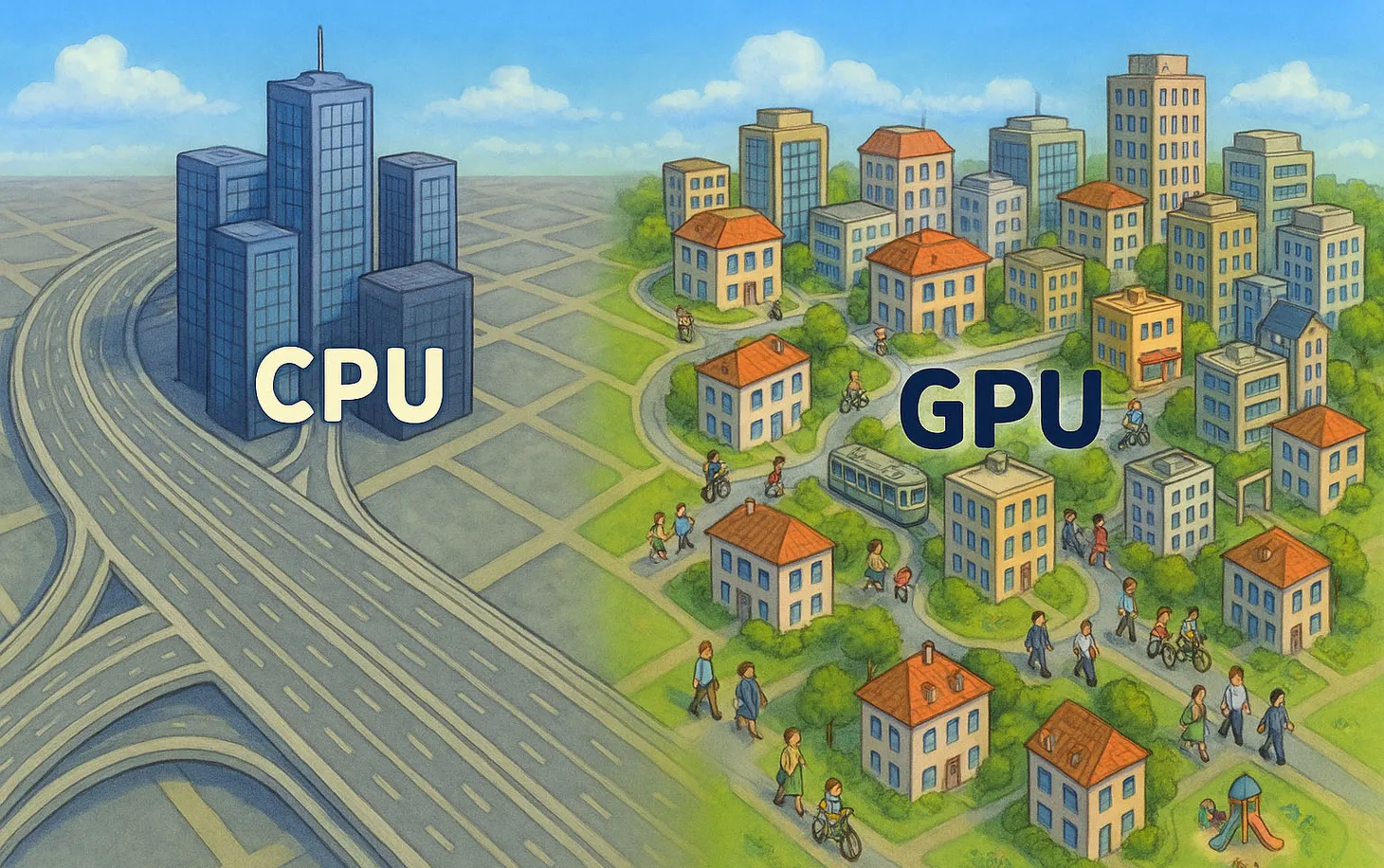

The under-utilization of resources should be as much of a concern as the over-utilization of resources. This is true for physical property, such as beaches and streets, but it is also true for intellectual property, such as software and ideas. In the world of artificial intelligence, there is currently a massive natural experiment concerning the benefits of open and closed approaches. The leading company in the space, OpenAI, runs on proprietary code and chargers customers using ChatGPT and its API. Meanwhile, Facebook just released a powerful large-language model that is entirely free for ~anyone to use and adapt as they please. Facebook's approach will create plenty of value for the public at large, but it is also likely to generate plenty of value for Facebook itself. Openness will lead to more experimentation, new products, better integration with other services, and possibly faster performance improvements. Here too, there is room for both approaches (open and private) to co-exist, but the balance between them will likely be healthier, with free and open being the default.

In the digital world, people can try out many different products and methods and jump between them at the click of a button. As a result, the traditional economic view makes more sense: resources are allocated to maximize their value in a manner that benefits their owners and society at large. In the physical world, most people are stuck in one place and cannot easily switch and experiment. And even when people want to change things, it is costly, politically fraught, and takes a long time. This means we should be extra vigilant in our fight against tragedies of the uncommon — we should constantly ask ourselves whether the current state of affairs is good, we should try to adopt openness and integration as the default, and we should design environments and systems that allow us to continue to experiment, rather than get locked in.

I should dive deeper into these ideas. What do you think? Are there any other angles here that I am missing? Any related examples I should look at? Let me know in the comments below.

Best,

P.S. — Want to master the latest AI tools for marketing, financial analysis, and general business automation? Check out my upcoming Practical AI Course.

Dror Poleg Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.