Navigating a Dancing Landscape

The internet compels us to constantly respond and adapt to each other's behavior. This makes everything less predictable. Why does this happen and how can we succeed in such an environment?

🎧 This article is too visual, so I did not record an audio version. But you can listen to other articles here.

The internet compels us to constantly respond and adapt to each other's behavior. This makes everything less predictable. Why does this happen, and how can we succeed in such an environment?

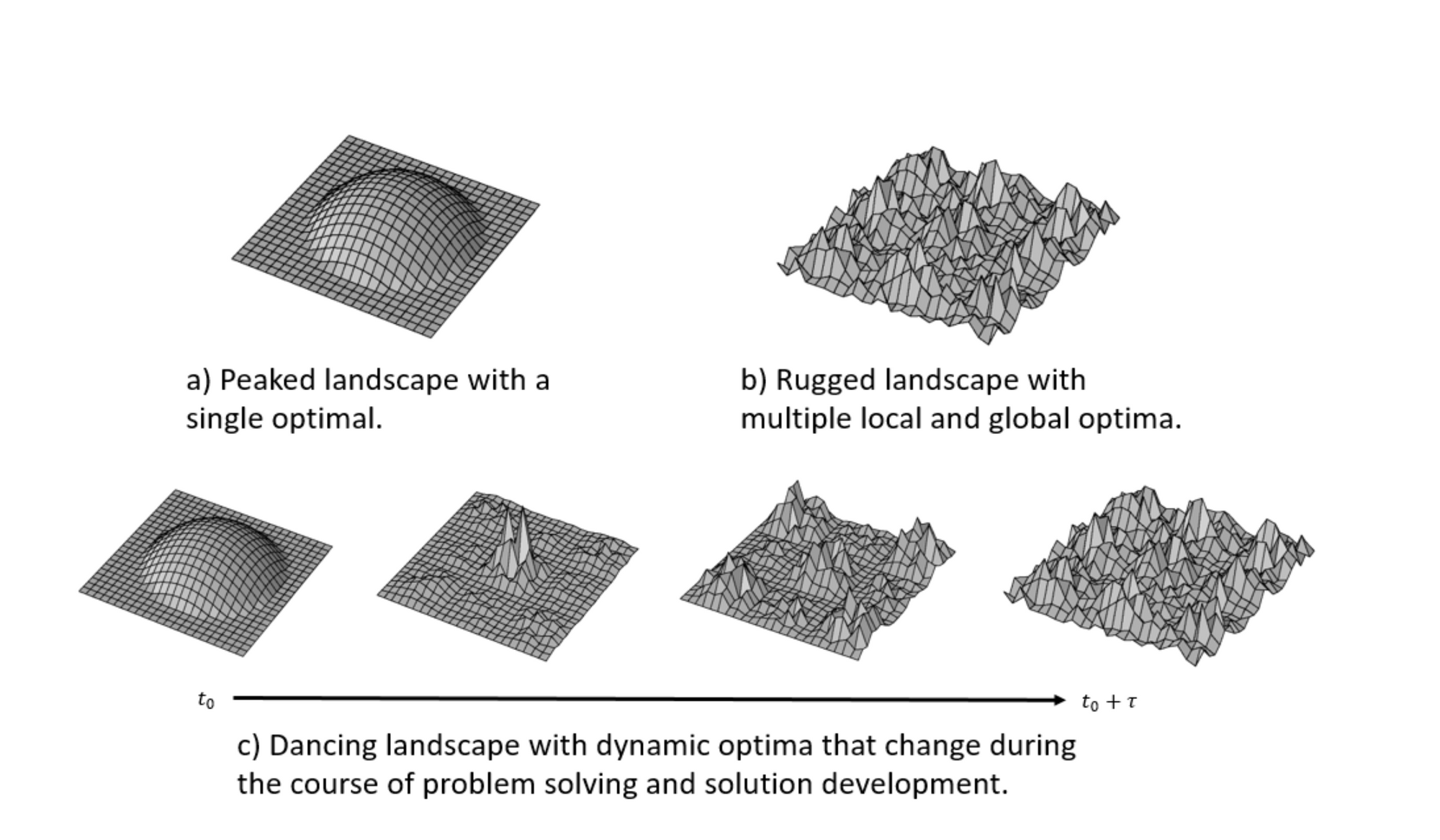

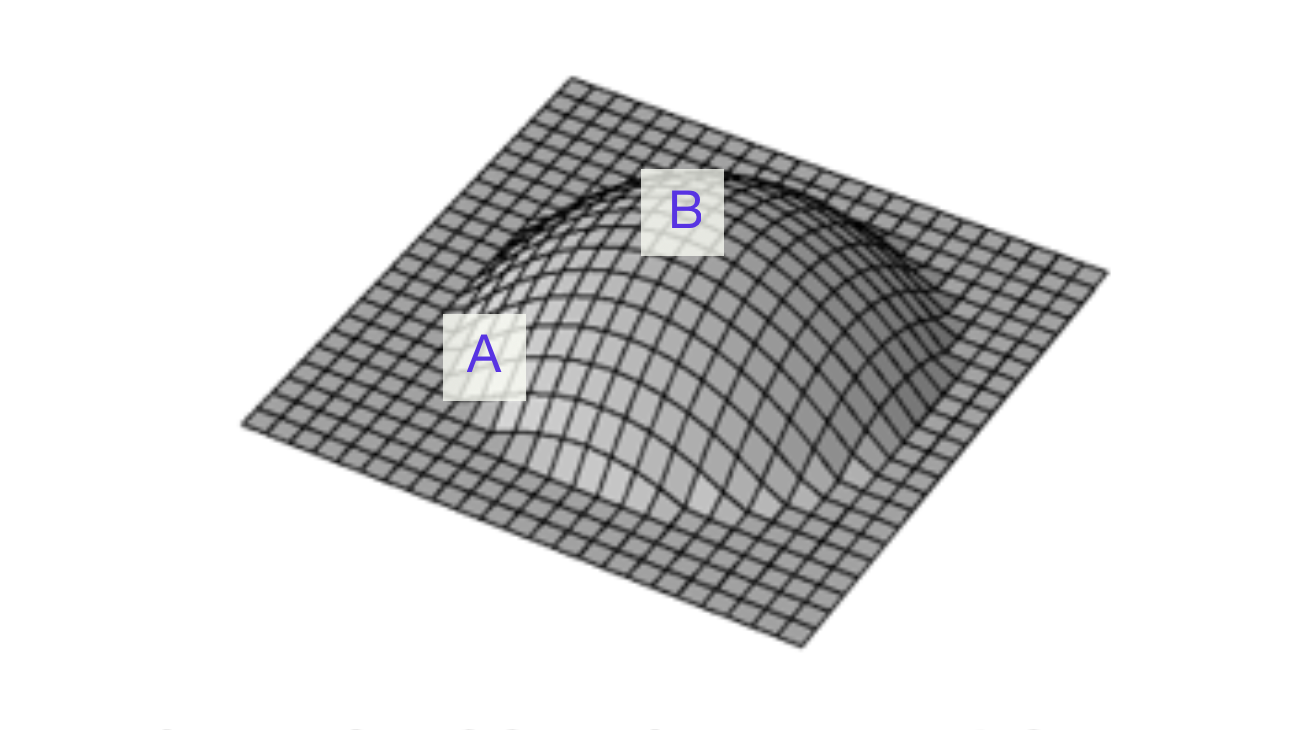

First, let's understand some key terms. Evolutionary Biologists use "fitness landscapes" to represent how well an organism's DNA is suited to its environment. The higher you are on the map, the more "fit" you are — and the more likely to prosper under current conditions. Below are some illustrations of different kinds of fitness landscapes.

Let's use an example to make sense of these landscapes, starting with something simple. Imagine two penguins with different DNAs. Penguin A can run faster, while B can swim in cold water. Given their environment and available food, penguin B is more "fit," while penguin A is not likely to survive. Visually, we can represent their respective fitness as follows:

Penguin B is at the top of the landscape, representing the highest fitness level, while penguin A's lower fitness is represented by a lower location on the "hill." Each penguin's DNA can be thought of as an evolutionary "strategy." In our example, there is only one path to success: If you can swim, you "win," regardless of whatever else you or anyone else does.

In business terms, we can say that strategy B is the clear winner. The better you are at swimming, the more likely you are to survive and thrive. But in reality, things are often more complicated.

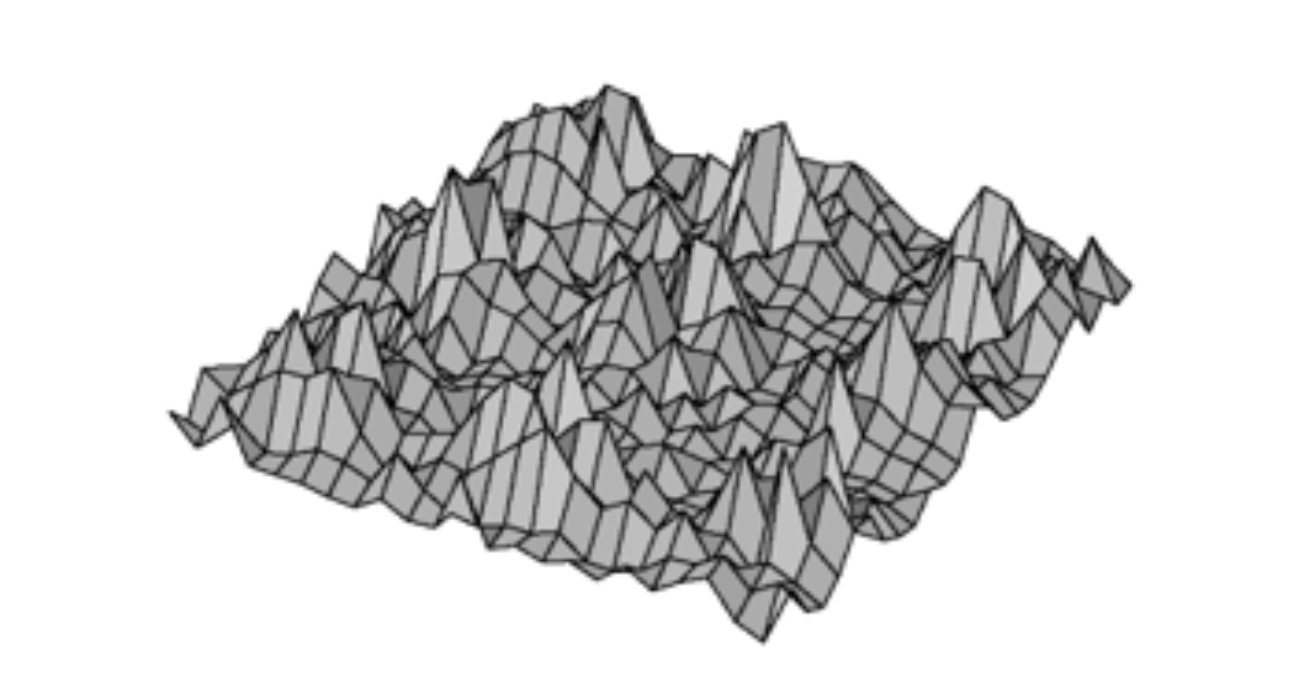

In many situations, the best strategy relies on a combination of traits and behaviors. A penguin can be a slower swimmer but have more stamina, a shorter beak, or better coordination. Minor differences and interactions between traits can lead to significant differences in fitness.

In such cases, the fitness landscape is no longer smooth with a single peak. Instead, it is rugged: Many different strategies can lead to success. And success is more dependent on the balance between traits rather than the absolute strength of any individual trait. Increasing your swimming speed might "push" you up to fitness "mountain." Still, at some point, it might also lower your fitness if it comes at the expense of other traits (for example, you lower your body fat in order to swim faster, but that reduces your resistance to cold and reduces your overall odds of surviving).

Rugged landscapes are common in business. There are many paths to success. A Big Mac can have less meat but more mayo and sesame than a Whopper. One manager can succeed by relying on superior memory, while another succeeds by being more organized. You get the idea.

But life gets even more complicated. Our environment is adaptive. Every action we take affects the behavior of everyone around us — often in a way that diminishes the effectiveness of our strategy. Every step alters the playing field. Biologists call this a "dancing landscape." (visualized by Tim Berglund)

On a dancing landscape, the optimal strategy constantly changes. It's hard to know what to do more of. Dancing landscapes describe complex environments where many organisms are interconnected and interdependent.

Is this complexity new? You can argue that the business world has always been complex, with firms and consumers constantly adapting to changing conditions. That's true. But there is something new about the level of complexity we now face for three main reasons.

The first reason is that we are running out of simple problems to solve. The world has always been complex, but one could become successful by focusing on "smooth landscape" problems. What does this mean in practice?

The history of work offers a hint. Frederich W. Taylor was the intellectual godfather of the industrial world. He pioneered "Scientific Management," which aimed to optimize output by rearranging how employees were located and redesigning the tools they used.

As professor Scott E. Page points out, Scientific Management assumes that there is one "best" way to perform any task and that this way can be determined through scientific analysis and study. In other words, Taylor focused on smooth landscapes — problems that yielded to a single optimal strategy.

Famously, Taylor ran a series of experiments to determine the optimal shape and weight of a shovel. He then redesigned coal shovels based on his findings. Employees who used Taylor's "scientific shovel" were 3-4 times more productive.

Taylor's work had a significant impact on the industrial world. His approach transformed linear work — when it was easy to establish a clear relationship between input and output. But work in the 21st Century is far less linear. And it has two other fundamental distinctions.

The productivity of a coal shoveler in Chicago is not affected by the productivity of a coal shoveler in Manchester. But in many modern jobs, a single person's ultimate productivity is dependent on other people's actions elsewhere. Let's illustrate this point with an extreme example.

Imagine your boss tasked you with increasing the sales of cranberry juice among middle-aged blue-collar workers. Your sharp instincts lead you to create a video of a dude on a skateboard, sipping juice, listening to Dreams by Fleetwood Mac. What's wrong with this strategy?

To start with, there's a non-linear relationship between the measurable input into the video and its ultimate success. This means that the only way to know whether a strategy works is to try it. But there's an even bigger problem.

Once you discover the best strategy, your competitors immediately copy it. Many brands (and individuals) start using the same song and style and steal attention away from your video. Your success is diluted as the landscape immediately shifts.

This example illustrates how the world is getting more connected AND how we increasingly deal with non-physical goods such as software and media. Such goods can be produced and altered quickly in response to your actions. The result is an unprecedented level of complexity.

Of course, most workers aren't tasked with creating viral videos. Most people still work in producing physical goods or providing various services. But the dynamics that govern the spread of viral videos play a growing role in determining what goods and services people consume. In other words, the complexity of the online world affects all of us, whether we like it or not.

Does it mean we're doomed? No.

Does it mean our careers will become a series of pathetic experiments to go viral?

Experiments, yes. But they don't have to be pathetic. Science offers some hope. And the non-physical nature of our economy has some unique advantages.

In nature, scientists observed several strategies that help navigate a dancing landscape, including:

- Stay flexible and respond quickly

- Hedge your bets but develop several strategies in parallel (learn to swim and don't forget how to fly or run)

But humans have a unique advantage. Animals in nature have constraints that no longer apply to us. In nature, the speed and scope of adaptation are constrained by the physical world. It takes generations for a genetic mutation to prove itself. And it is time-consuming and difficult to try anything new.

Our non-physical, non-linear world is different: We can try many different strategies cheaply and quickly and see what works. In other words, we can employ a meta-strategy: The strategy of trying many different strategies. So, Tweet, upload, share your ideas, and try to navigate your way. It doesn't cost much, and the rewards are infinite.

This doesn't sound fun?

There's a fourth strategy that you (and all of us) can try. As mentioned above, the landscape is dancing because we're all interconnected and interdependent. You can reduce the "dancing" by reducing the number of connections and dependencies.

How do you do that?

One way is to specialize in tasks that are constrained by the physical world. Another is to rely on a network that is constrained by the physical world. In other words, sell a physical service that is relevant to people in a specific location.

Will this protect you from automation and encroachment of online competitors? Not entirely, but it might buy you some time. And more importantly — you might enjoy it.

Have a great weekend. If you enjoyed this piece, subscribe to ensure you don't miss the next one. You can also follow me on Twitter for sneak peeks of future posts

Dror Poleg Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.