Still In Praise of Ponzis

The bubble has popped, but pyramid schemes are more important than ever. If you want customers to notice you, you'll have to play along.

🧠 Last week, I wrote about technology's growing role in generating and spreading destructive ideas. I am still working on the follow-up piece that looks at what governments and corporations can do to maintain social stability and protect their interests. Subscribe, so you don't miss it.

🧑🏻💻 I had a lively conversation with Stanford Professor Nicholas Bloom about remote work and its impact on cities, offices, and inequality. You can watch the recording here.

🎧 Last month, I was on Professor Scott Galloway's podcast to talk about inequality, human capital, banning TikTok, the future of work, and the future of cities. If you haven't listened yet, I recommend it. Listen here.

📚 In late November, I'll be teaching the 8th cohort of Hype-Free Web3, a two-week course about the future of the internet and emerging business models. It's an updated version of the course, shorter, tighter, and considering all the recent regulations and innovations of the past six months. Learn more and sign up here.

And speaking of Web3...

For the second time in its history, Bloomberg Businessweek dedicated a whole issue to a single topic, written by a single author. The topic is Crypto and Web3, and the writer is Matt Levine, the world's preeminent finance writer.

Matt is and has been a crypto skeptic. Still, he also understands why the Web3 space is important and why it should be explored by anyone interested in technology, finance, the future of work, and geopolitics.

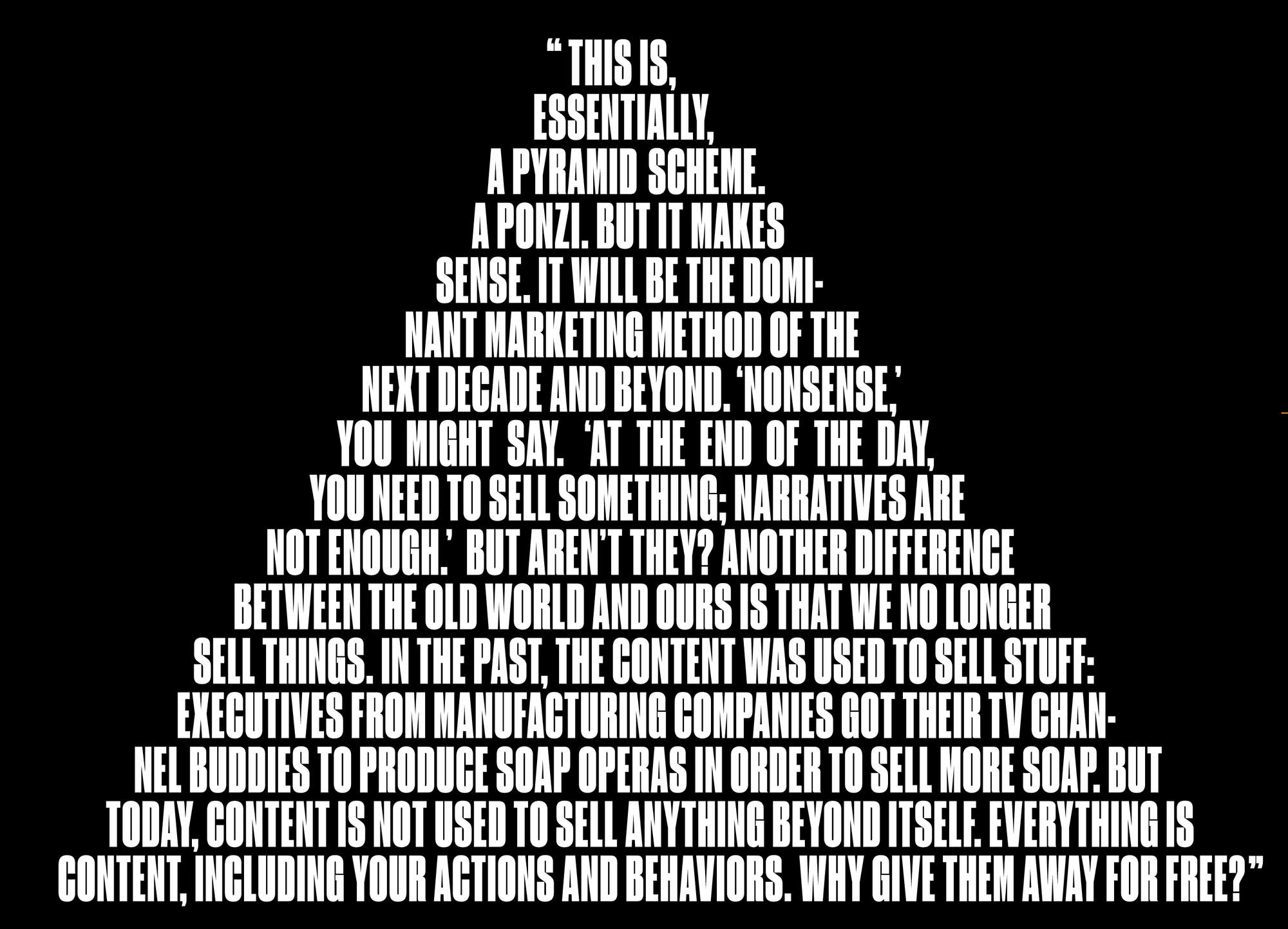

In the piece, I was struck by the following quote from Matt:

"Dror Poleg, a writer on business and technology, wrote a blog post about web3 that I think about all the time. The title is 'In Praise of Ponzis.'"

Matt is referring to a controversial article I wrote last year. His Businessweek opus featured a massive graphic with an excerpt from my earlier article:

Many people are still trying to wrap their heads around what I meant. I was not praising the idea of marketing things that don't exist. I was pointing out that, whether we like it or not, the economy is increasingly reliant on selling things that don't exist.

More precisely, more of our money is spent on things that are not physically scarce: content, attention, virtual goods, and knowledge. In a world of such abundance, success is no longer about who can produce the most goods or the "best" goods at the lowest price.

Instead, success depends on who can cut through the noise and get people's attention. To do that, one often requires the support of a critical mass of people at a crucial time: Getting your product (physical or digital) liked and shared by an X number of people can trigger a cascade: Social media algorithms show the product to more people, who then like it and share it, which causes algorithms to boost it even more — resulting in massive success.

Note that the people who liked and shared your product played a critical role in making it successful. Often, this role was more important than the product's design or production.

But historically, the people who like and share stuff on social media are not compensated for their "work." This is (was) the case for two main reasons:

- People's likes and shares were not so important. In the old world, things were scarce, and the most important activity was to actually produce stuff. Getting some promotional help from early users was nice, but it wasn't the deciding factor.

- Even if you wanted to compensate people for every "like" and "share," this would have been too complicated and expensive to do in practice. (imagine getting the bank details of every user and sending them a wire transfer or check for 35 cents each time they liked a video. It doesn't make sense)

But today, likes and shares are critically important. And the cost of tracking people's behavior and sending them micropayment is close to zero. To win, a growing number of companies will have to incentivize people to like and share (and use) their products. They will have to make it worthwhile for customers to jump on the bandwagon early and ensure that early users benefit from every new user that jumps on board after them.

The result is a pyramid: A system that incentivizes people to convince others to follow them into a financial scheme. And as I pointed out in my original piece, such pyramids will be the dominant marketing method of the next decade and beyond.

Not because there's a bubble. And not because of low-interest rates. But simply because our economy is shifting towards intangible goods and because such goods will be available in abundance. Further, even the marketing of tangible goods will be increasingly dependent on digital content. If you want to sell a car, a house, or a hamburger, you probably need to draw people's attention to a video or social media post. If people don't notice you online, you don't exist. And for people to notice you, you'll need to share more of your revenue with anyone who helps promote your content.

Have a beautiful weekend.

Dror Poleg Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.