Cities are Instagram

As they grow, networks become more efficient and less egalitarian. The process explains a lot about where we are — and where we're headed.

🗞 Over at Forbes, Professor Rick McGahey quotes and weighs in on my recent thinking about the future of offices and cities. Read it here.

🎧 An audio version of this article is available below and on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, and beyond.

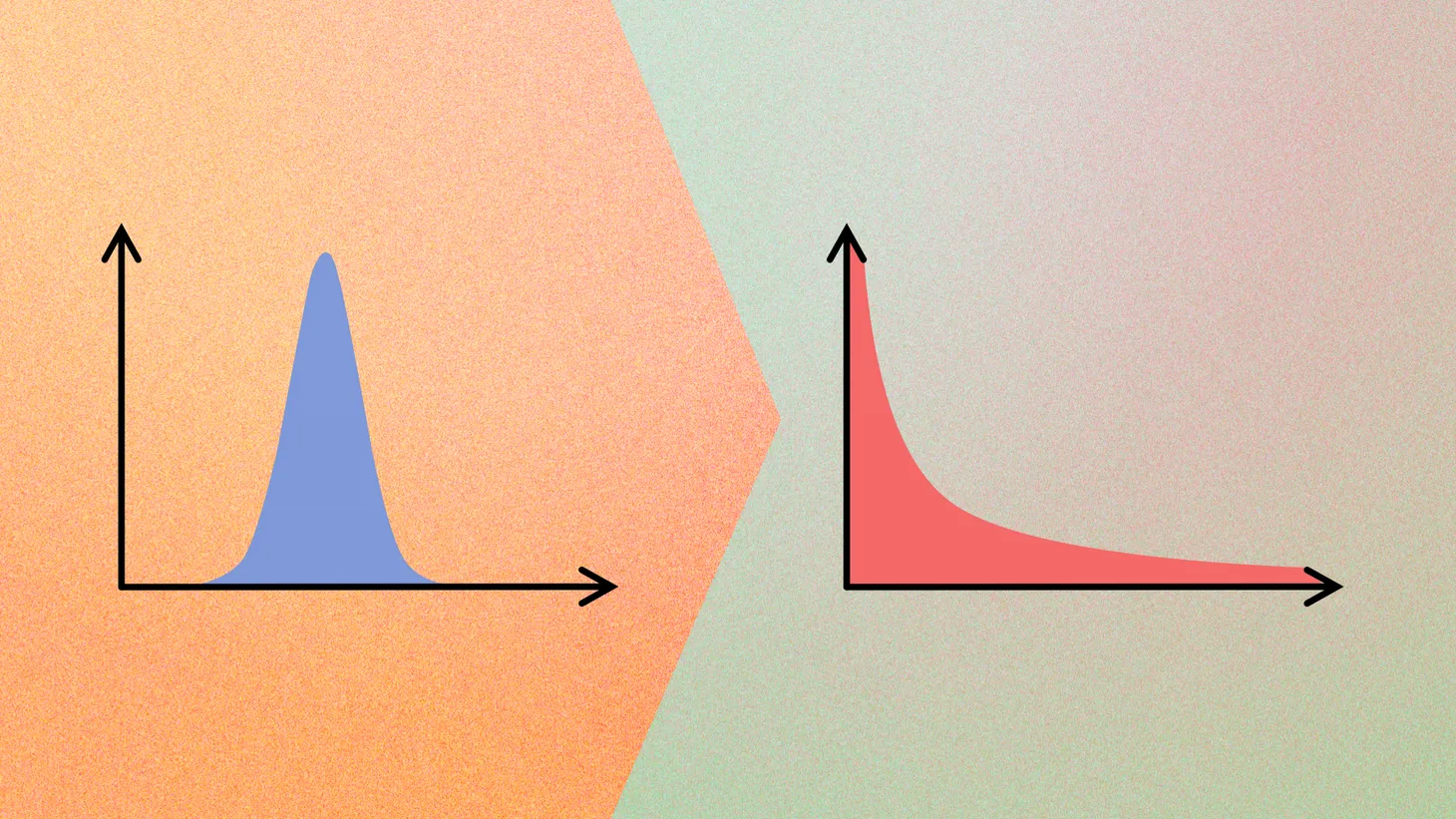

Productivity and inequality are often two sides of the same coin.

As cities grow, their economies tend to become better at producing valuable ideas, and their income inequality tends to increase.

Why is that?

The answer holds the key to our future.

Many factors contribute to the scaling of urban productivity and inequality. Economists and politicians tend to focus on narrow aspects that make some things better or worse. But there is a more fundamental reason: Cities are networks.

Why do (some) networks become more productive and less egalitarian as they scale?

Because from a network's perspective, inequality is often the most efficient arrangement. To understand this in practice, let's look at a social network — Instagram.

What is the purpose of Instagram? It depends. For shareholders, the purpose is to produce as much revenue as possible. For advertisers, it is to get as much exposure for the lowest amount of money. For users, it is to get entertained.

For simplicity's sake, the purpose of Instagram is to generate as much user engagement as possible for the lowest possible cost.

To achieve this purpose, Instagram needs to do two things well:

- Enable as many people as possible to create content

- Boost content that has the highest potential to generate engagement

Instagram also needs to do a 3rd thing, but we'll leave that for later. For now, we can ask: What is the outcome of Instagram's two key actions?

The more people post on Instagram, the more productive it becomes in achieving its purpose and the more unequal the distribution of likes and attention among its users.

Why is that? More posts result in a higher likelihood that one of the posts will be incredibly engaging. More users mean more potential viewers for that incredible post. As Instagram scales, it has better content that can be shown to a larger number of people.

Inequality is a direct consequence of Instagram's efficiency. The ability to show better posts, made by a handful of winners, to a larger number of people is both efficient and unequal.

But it doesn't stop there.

Instagram users copy, reference, iterate on, and refine each other's ideas. Hence, the larger the network and the more interaction between users, the more likely it is that an "incredibly engaging" post will be created.

The same is true in cities. From an economic perspective, the purpose of a city is to turn limited input into maximum output. The input can be people's time, money, or natural resources.

To achieve this purpose, cities need to do two things well:

- Enable as many people as possible to provide input

- Boost input that is more likely to generate valuable output

"Valuable," in this case, means whatever consumers are looking for — from the best doctors to cheap snacks. Cities do the above well because, like Instagram, they enable entrepreneurs to copy, reference, iterate on, and refine each other's ideas.

Hence, the larger the city and the more interaction between users, the more likely it is that valuable products and ideas will emerge. And just like on Instagram, urban inequality is a function of efficiency. The ability to distribute better goods and services, made by a handful of winners, to a larger number of people results in higher efficiency and inequality.

But is that really how it works? It's a bit more complicated. Everything we have covered so far raises two questions or objections:

- Instagram only compensates winners. But everyone on Instagram is "Working." Isn't that inefficient?

- It's not clear that Instagram or cities are good at identifying the absolute best content, ideas, and performers. Doesn't luck or chance play a significant role here?

Let's start with the second objection. It's true: Larger networks are worse at identifying the absolute best performers and ideas. To understand why, let's look at a simple example.

Imagine trying to find the best doctor in a village with 500 inhabitants. You ask around and find someone. What are the odds that the doctor you found is the best doctor in the village?

I'd say close to 100%.

Now imagine you're trying to find the best doctor in New York City, a city with close to 9 million people and tens of thousands of doctors. You ask around, Google, and find someone. What are the odds that the doctor you found is the absolute best doctor in NYC?

I don't know, but the odds are much lower than 100%.

If you're really sick, does this mean you should look for a doctor in a small village rather than in NYC?

Intuitively, you already know the answer. But let's put the question differently: Which doctor is likely to be better, the one you can find in the small village or the one you can find in New York City?

Most probably, the NYC doctor is better.

The same is true for engineers, bakers, teachers, and many other professions. This is not a diss at small villages; it is a simple statistical fact: In a large pool, sampled from the same population, you're less likely to find the absolute best performer, but even the 2nd or 20th best is likely to be better than the best performer in a much smaller pool.

This has two important consequences:

- In a more extensive network, luck/chance plays a more significant role in determining who gets to be #1 (number one).

- Because large networks are more efficient, the rewards for achieving the top spot will likely be much higher than those given to #5 or #500.

This brings us back to the first objection. Beyond the handful of big winners, everyone on Instagram is "working" by producing content and providing feedback. Isn't that inefficient?

In a narrow sense, having lots of people work for little or no reward can be considered efficient. But it is not fair, and it is not sustainable.

This is true for cities as it is for social networks: In large networks, winners emerge thanks to the input and complex interaction between millions of people. Most of these people are under-compensated for the input they contribute to the network.

A lottery is a great example of this dynamic: Big winners exist only because everyone else bought a ticket. This is true even if some winners have unique traits or skills that increase their odds.

In their current form, cities and social networks over-compensate a small number of winners at the expense of all other participants (including those with very high merit). And it's about to get much worse.

But before we get to that, let's take a moment to understand why this is not sustainable. Let's stay with the lottery example: A lottery only works when enough participants believe they have a chance. The game continues as long as enough people are willing to buy tickets and participate. Further, the game continues as long as enough people are able to buy a ticket — that enough of them are alive, healthy, and have the capacity to try.

How close are we to the point where this is no longer the case?

It's not clear, but we seem to be getting closer. And why will it get worse? Because both cities and Instagram are relatively small or constrained. In the case of cities, their size is limited by the physical world, so they can't become that much bigger. In the case of Instagram, it can encompass billions of people, but it constrains them to relatively low-stakes interactions.

But there's another network that is larger than Instagram and is as critical to our safety and livelihood as the physical world. That network is the internet itself. The more connected we are, the more we become dependent on the dynamics that govern that large network. And the more likely we are to witness the emergence of a relative minority of large winners while the rest of us fall behind.

Note the word "relative." The network might become more efficient as it pulls the whole global economy into it. In aggregate, humanity will likely become wealthier as a result. But individually, we might feel like we're getting poorer like we no longer have access to the best the world has to offer. As a result, many of us might choose to step away from the game or try to burn down the playing board.

How do we reap the benefits of efficiency without suffering the consequences of the network's inherent inequality?

More on that next time. Subscribe, so you don't miss it. Can't wait for the next article? Follow me on Twitter for something to nibble on in the meantime.

Dror Poleg Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.