Perpetual Gamma Squeeze

A "crowd with a bank account" is turning the economy — and society — on its head.

A "crowd with a bank account" is turning the economy — and society — on its head.

The internet of information made it possible to manipulate markets at scale. The internet of money will make it necessary for everyone to participate in such manipulations.

When large groups of people can join forces and channel their money towards goals they care about, the old distinction between market participation and market manipulation is no longer valid. And once enough people partake in market manipulation, all other market participants must respond in kind.

But the manipulation of existing markets is just the beginning. The internet and blockchains enable people to buy and sell anything — JPEGs, videos, blog posts, data, attention, gestures. This gives rise to whole new markets that are even more susceptible to manipulation by coordinated crowds.

And it will not end there. Ultimately, this process will affect the most important market of all — the market for ideology and political power. To figure out where we're headed, we begin by looking at how coordinated crowds affect financial markets.

Options 101

Stock options are a form of leverage. They enable people to express a point of view, earn a lot when they're right, and lose (relatively) little when they're wrong.

Let's assume I believe that Apple shares will increase from $170 to $200 price over the next two months. I can buy Apple shares for $170 each. Two months later, if the stock increases in value to $200, I can sell and gain $30 per share in profits. If the price goes down to $140, I can sell and lose $30 per share. If the price goes to zero, I lose the whole $170. In this scenario, I risk $170 per share in order to gain $30, or a 17.6% return.

Alternatively, I can spend $9 on the option to buy an Apple share for $170 two months from now. If, within two months, Apple's share price increases to $200, I can exercise my option, buy the shares for $170 each, and then sell them immediately for $200. In this scenario, I will earn $30 for every Apple stock I buy, minus the $9 I paid for the option. In other words, I risk $9 and gain $21, or a 133% return.

Options also have downsides, most notably the fact that they expire at a specific date. If the stock does not reach my target price by the expiration date, I will be left with nothing. Still, the leverage offered by options is attractive for many investors — in the same way, a slot machine is attractive to many gamblers. Both options and slot machines offer people the chance of winning big while risking little.

But there's a key difference between casinos and financial markets.

Static and Dynamic Markets

In a slot machine, the odds are fixed. A coordinated group of 100 people decides to pull the lever of 100 slots machine at the same time; each person's odds will be identical to those of any random person who plays alone. In financial markets, on the other hand, the behavior of each individual participant affects the odds of all other participants.

In theory, a group of 100 people who decide to buy the same stock simultaneously can kick off a market dynamic that drives up prices and turns all of them into winners. In practice, this type of market manipulation has a long history: In the 1920s, a group of investors bought and sold RCA stocks "among themselves to build a record of increasing volume and prices to sucker in other people"; In 2021, members of the WallStreetBets subreddit (discussion board) joined forces to push up the value of Gamestop and AMC.

But the Redditors weren't simply buying shares in order to entice other people to buy shares and drive the price up. Instead, many of them were buying options in order to increase their leverage and force large investors to buy more shares.

That last point is essential to understand. When people buy options, whoever sells them is taking a risk. If I sold you a contract that gives you the right to buy Apple shares at $170 at some point in the future, and Apple shares end up being worth $200 at that point, I will have to buy shares at $200 and sell them to you for $170.

To hedge this risk, option sellers usually buy (or sell) stocks to offset their exposure. In the example above, the seller of an option might buy some shares at $170 to have them available if the buyer decides to exercise their option at some time in the future. In other words, the buyer of the option is causing the seller of the option to buy a proportional quantity of the option's underlying stock.

This is comparable to two people of equal weight tugging at a rope. If one of them leans backward, the other one has to lean back as well just to remain in the same place.

And it doesn't end there. When a buyer buys a riskier option, he can force the seller to buy an even higher number of shares. For example, if Apple's current price is $170, and I buy an option to buy 100 shares at $150 at some point in the future, then the seller is at risk of losing $50 per share if the price ends up going to $200. To hedge this risk, the seller will have to buy more than 100 shares at the current price.

A mechanism that lets investors force other investors to buy a specific stock sounds like a recipe for trouble. But in reality, these types of trades don't have a significant impact on share prices because (1) they're relatively small compared to the overall trade in a given stock; (2) options are priced using a sophisticated formula that discourages people from buying "out-of-the-money" call options with a strike price above a stock's current market value; and (3) it's unlikely that enough people will trust each other to jump into a trade that doesn't make sense unless everyone else follows through. These three mechanisms worked reasonably well until the internet came along.

The Reasonable Madness of Crowds

The internet gives people the power to coordinate the buying of options at a scale that can overwhelm the market in a specific stock and to do so at a price that reflects unreasonable risk. This, in turn, forces large option sellers to quickly buy larger quantities of an underlying stock, resulting in the price moving up.

When the price moves up, more buyers sometimes pile onto the trade, in expectation of further increase. The option sellers are then forced to buy even more stocks to hedge their increased risk (if they sold an option to buy at $170 and the price has since moved up to $180, they have to take action just to remain "neutral"). This creates a stampede that can push a stock's price very far up, very quickly.

This type of stampede is called a "Gamma Squeeze" (after the Greek letter Γ that denotes the rate of change in an option's risk sensitivity). A well-coordinated crowd can instigate a Gamma Squeeze and reap significant rewards.

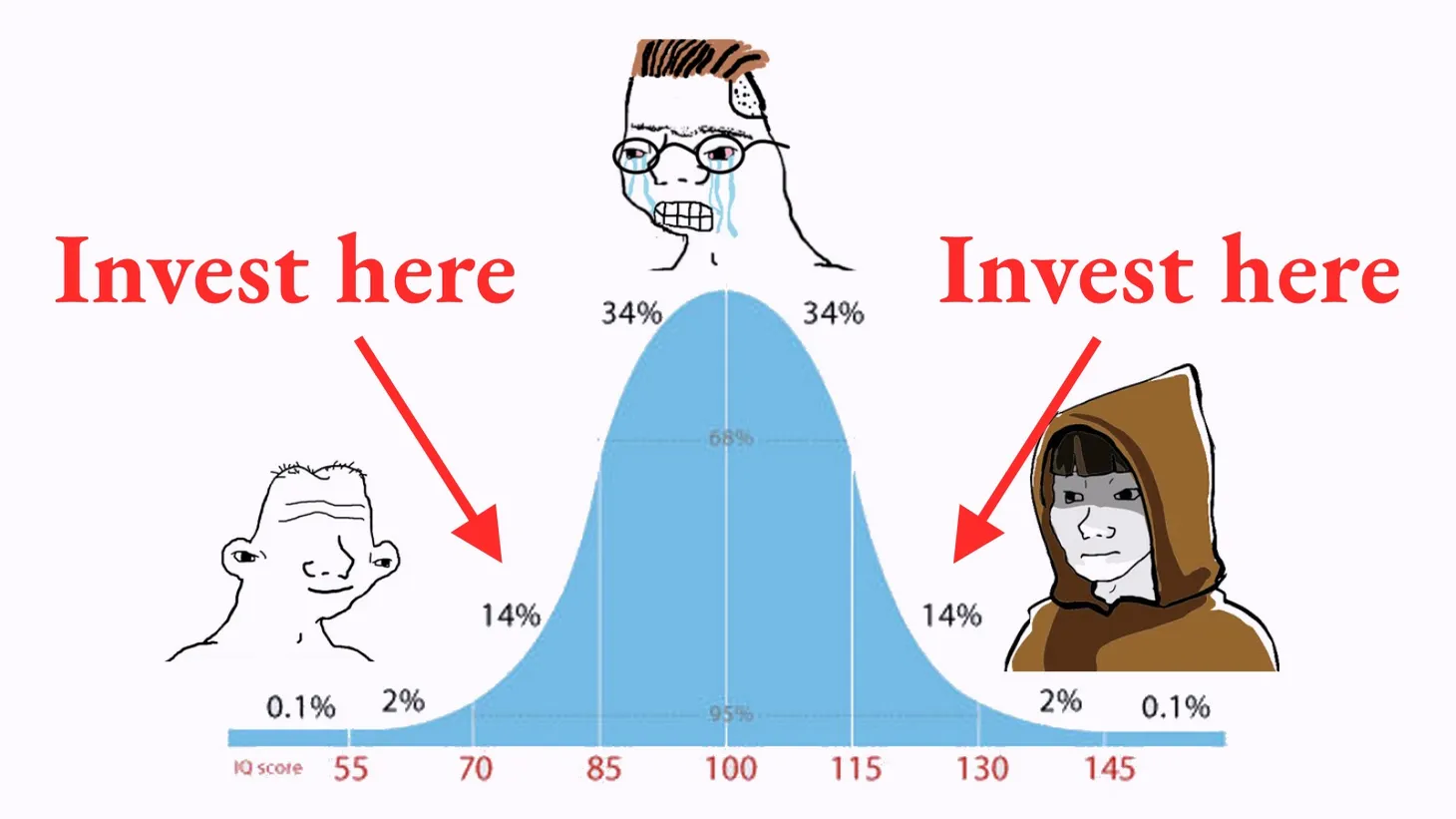

But wait, we noted that option contracts are priced to discourage buying "out-of-the-money" positions and that buying such positions in high quantity represents an unreasonable risk. If so, why would a large group of people take such a risk? Simple: By taking this risk together, the buyers are actually reducing their risk. When one person buys an out-of-the-money option, he is in danger. But when 10,000 people buy such an option, it's more likely to result in a "Gamma Squeeze" that pushes their options "into the money."

In other words, when enough people do something unreasonable, it becomes reasonable. But how do you convince enough people to do something unreasonable?

Memes and Markets

In 1976, Richard Dawkins coined the term "meme" to describe "a unit of cultural transmission" — ideas and behaviors that replicate through imitation. Dawkins saw memes as the cultural parallel to genes:

"Just as genes propagate themselves in the gene pool by leaping from body to body via sperms or eggs, so memes propagate themselves in the meme pool by leaping from brain to brain via a process which, in the broad sense, can be called imitation."

Dawkins's original ideal was later refined and expanded to explain why certain ideas and behaviors spread while others don't. Characteristics that increase a meme's chances include:

- Being useful or appearing to be useful (to the humans who "adopt" them);

- Being easy for humans to imitate;

- Having a tendency to change the environment to the detriment of other, competing memes (for example, a conspiracy theory that pre-empts or undermines any future information that may debunk it);

- Answering questions that humans find interesting; and

- Acting symbiotically with other successful memes (for example, a conspiracy theory that builds on an existing popular notion or a song that remixes bits of an already-popular song in a way that makes both of them more popular)

Financial markets are fertile ground for memes that tick all of the above boxes. In 2021, memes drove thousands and, possibly, millions of people to buy shares and out-of-the-money options of AMC and Gamestop. These two stocks were considered hopeless and faced intense short interest from Hedge Funds and traditional investors who expected their value to continue to drop.

The memes that encouraged people to buy and prop up AMC and Gamestop spread quickly because they were useful ("make money!"), were easy to imitate ("buy this stock!"), changed the environment to the detriment of competing memes ("Wall Street and mainstream media are the enemies!"), answered questions that humans found interesting ("how can I make more money?!"), and built on other successful memes (the notion that financial markets are rigged against little people).

The whole operation was enabled by memes spreading over the internet — broadly and quickly — and by online brokerages that made it free for people to buy and sell stocks. The result, in both cases, was a Gamma Squeeze that pushed stock prices "to the moon." And once prices reached the moon, they dropped quickly — leaving many members of the original "crowd" with losses or only limited gains.

As Spencer Jakab pointed out in the WSJ and in his new book:

"The GameStop surge was often portrayed as a triumph of amateurs over professionals, fueled by social media...

They circulated memes showing images of their favorite companies superimposed on the surface of the moon, representing how high they wanted the stock to climb. They said they wanted to defy the hedge funds that bet against these stocks...

Some of those small-time investors did make money... And some on Wall Street fared poorly...

When the smoke cleared, though, the popular image of tables being turned on America’s financiers wasn’t entirely accurate. Individual investors who bought GameStop this time a year ago and never sold are sitting on hefty losses."

The internet enables crowds to spread their ideas and loosely coordinate their actions. This is meaningful, but it has a limited impact. To maximize their impact, crowds need to coordinate their actions with more precision and target markets that are more susceptible to manipulation. And that's exactly what's happening now.

Wallets and Wallpapers

Decentralized Autonomous Organization (DAO) is a fancy name for a simple idea: a digital "bank account" that lets multiple people pool their funds and control how these funds are spent. By "control," I mean set clear rules and ensure these rules are enforced. A DAO is essentially a piece of software that handles money. You can specify in advance that the DAO would only accept deposits from people who meet certain criteria and that the money will only be spent if, say, 65% of all DAO members agree. DAO members can also vote to hire people or give specific members the power to take certain actions.

As critics often point out, a DAO is simply "a crowd with a bank account" — it's a mechanism that enables an unlimited number of complete strangers to share a wallet. Software code makes it unnecessary for these strangers to trust each other — it verifies each of them contributed what they promised, and it ensures everyone's funds will only be spent based on pre-specified rules. In other words, DAOs enable increased coordination among strangers.

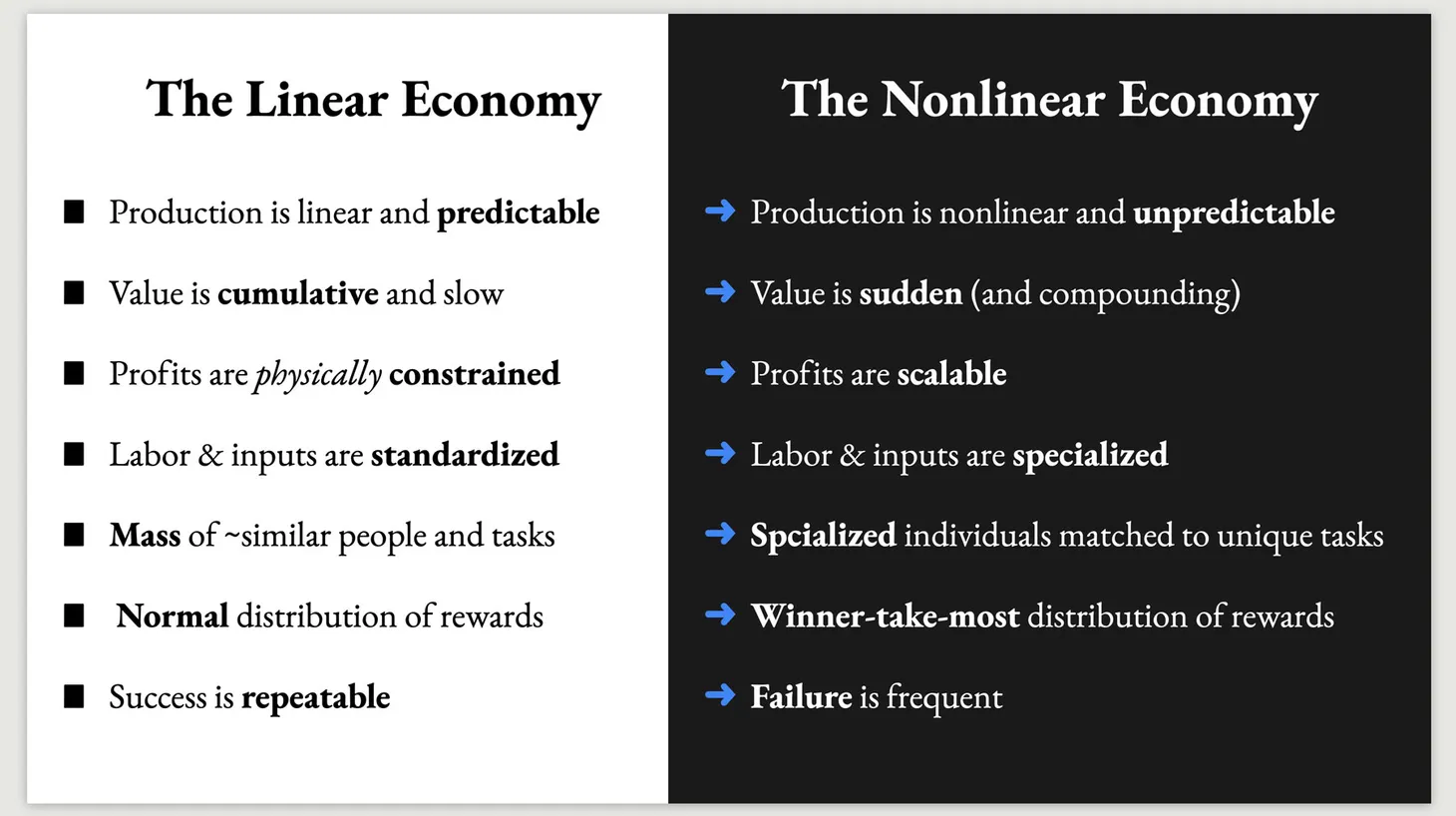

A crowd with a bank account doesn't sound like a big deal until you realize that coordinated efforts by large groups of people can move markets. Traditional financial markets are just the beginning. They are actually less interesting because they have:

- clear, objective frameworks that define how stocks should be valued;

- large and powerful players; and

- laws and regulators that tend to favor those powerful players.

As a result:

- even the best meme in the world cannot convince enough people that a bankrupt company is worth more than it does;

- a crowd with $1 billion is still a relatively small player; and

- any successful market manipulation is likely to draw scrutiny and litigation.

But there's much more to life than financial markets. Another popular criticism of cryptocurrencies and tokens is that "they financialize everything" by making it possible for people to buy and sell JPEGs, videos, blog posts, virtual clothes, gestures, and more. In contrast to traditional financial markets, the market for cultural goods is more open and more susceptible to manipulation: It has no standards of "fundamental value," no time-honored giants, and no regulation.

Monkey See, Monkey Do

If a million people decide to push up the value of a collection of monkey illustrations, there is no Goldman Sachs to push against them and no SEC to sue them for securities fraud. Further, if a billion people decide to like and share a specific video, you'll be hard-pressed to define their participation as manipulation.

As DAOs and tokenized goods become more prevalent, a growing share of economic activity will be subject to intense manipulation by "crowds with bank accounts." These crowds will make "unreasonable" actions such as promoting cultural goods that they decide to promote, in violation of the subjective laws of good taste (for example, driving the value of a collection of monkey JPEGs to exceed that of the Mona Lisa).

Conversely, anyone who tries to invest without teaming up with other people — without partaking in market manipulation — will actually be taking on higher risk. As more people join crowds to manipulate markets to their benefit, what will determine which crowd wins? The memes, of course. The crowd with the most compelling memes will be able to recruit the largest number of people (or amount of money) and impose its will on everyone else.

This process will be ongoing, with crowds forming and dispersing to take on different opportunities. It will just be one more way in which the internet offers new opportunities to win and lose — but fewer opportunities to avoid risk.

But the financial risk is only the beginning. People don't just invest in stocks and digital goods; they also invest in ideas. And some ideas are dangerous.

More on that, next time. Subscribe so you don't miss it.

Thank you for reading. If you enjoyed this piece, please share it, subscribe to my newsletter, and check out my course.

Dror Poleg Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.