Rise of the 10X Class

The "robber barons" of the 21st Century are the people who used to sit next to you at the office.

The Split

Everyone is worried about the concentration of economic power in the hands of a small number of people. This discussion is usually focused on tech billionaires and the companies they created — Amazon, Google, Facebook, and to a lesser extent, Apple, Twitter, and even Tesla. But a less conspicuous class is about to amass vast economic power. That class is composed of working people who do not own companies or employ anyone else.

Before we get to them, let us consider what the source of rising inequality is. Alfred Marshal ascribed it to intelligence, luck, the availability of capital, and technological progress:

“two causes have cooperated to put enormous power and wealth in the hands of those business men of our own generation in America and elsewhere, who have had first-rate genius and have been favoured by fortune… the general growth of wealth and the development of new facilities for communication, by which men, who have once attained a commanding position, are enabled to apply their constructive or speculative genius to undertakings vaster, and extending over a wider area, than ever before.”

Marshal was one of the founders of modern economics. He wrote the above in 1890 (I rearranged the sentences to make them more coherent). The “communication” technology he was referring to included railways, steamboats, and the telegraph. The most famous “businessmen” who benefitted from their invention were the so-called robber barons that dominated “new economy” industries such as railroads, steel, shipping, banking, and oil.

Marshal had more sympathy for these “barons” than most, pointing out, for example, that Andrew Carnegie’s consolidation of multiple railroads “probably saved to the people of the United States more than he accumulated himself.” But this case, his main interest was not in the inequality between the common man and a handful of ultra-wealthy industrialists. Instead, he was interested in emerging inequalities within existing professions.

Marshal highlighted how “the relative fall in the incomes to be earned by moderate ability [was] accentuated by the rise in those that are obtained by many men of extraordinary ability” in service occupations such as barristers, solicitors, doctors, writers, singers, and jockeys.

In other words, he wondered why mediocre performers started making far less money while the best performers started making much more. “In all these occupations,” Marshal wrote in 1890, “the highest incomes earned in our own generation are the highest that the world has yet seen.”

Why did this happen? Marshal thought that “the general growth of wealth” was “almost alone” the cause. Industrialization created more disposable income (for some), and those who could afford the best service providers were willing and able to pay a premium.

Liz and Charli

It’s important to note that Marshal credited wealth accumulation by industrialists such as Vanderbilt to both technology and growth in disposable incomes. But when it came to the relative enrichment of service providers and entertainers, he did not consider technology an essential factor.

The reason is obvious: Technology made it possible for Vanderbilt to scale his railways across a huge market, with multiple lines running simultaneously and generating income while their owner was asleep. But technology did not enable, say, a barrister (trial lawyer) to scale in the same way. The latter’s wealth was constrained by his inability to be in more than one place at a time.

To illustrate this point, Marshal described the income earned by Elizabeth Billington. Billington was one of the most famous singers in the world. In 1801, she earned about £10,000, equivalent to £750,000 in 2020. Nearly a hundred years later, Marshal predicted that “so long as the number of persons who can be reached by a human voice is strictly limited, it is not very likely that any singer will” earn more for the same type of work.

Higher disposable income among the general public meant that more singers could earn higher fees. It meant that more people were willing to pay a premium to hear excellent — rather than mediocre — performers. But it did not change the maximum fee any given singer could earn. Creative, in-person jobs were just not scalable.

In 2020, things are very different. Charli D’Amelio, a TikTok star that 99% of you have likely never heard of, makes $48,000 per post. By uploading one short video every day, the 16-year-old D’Amelio can earn 20 times more than the world’s most successful singer earned in 1801. Charli is scalable in a way that was possible only for a tiny group of TV, film, and pop stars 20 years ago, and was not possible at all in Elizabeth Billington’s time.

But we’re not here to talk about celebrities and entertainers. We’re here to talk about regular working people. Before we get to that, let’s spend a few more minutes at the opera.

The World’s a Stage

“In the performing arts, crisis is apparently a way of life." So begins a 1968 study by economists William Baumol and William G. Bowen. The two professors sought "to explain the financial problems of performing groups and explore the implications of these problems for the future of the arts.” What they discovered ended up explaining much more besides.

Like Marshal, the newer study described how “the technology of live performance leaves little room for labor-saving innovations since the end product is the labor of the performer.” But Baumol and Bowen also noticed something else. Salaries in the performing arts sector continued to rise even though the industry as a whole did not become more productive. The output (a show) remained the same, but the costs kept going up. As a result, organizations that employed performers were under constant financial duress.

Compare this to the automobile industry. Labor and other costs have gone up there as well. But companies in that sector were constantly becoming more productive, figuring out ways to churn out more widgets for the same number of working hours. The increase in productivity made it possible to absorb higher labor costs. Over time, a car company could grow its output and business while reducing its overall number of employees.

Meanwhile, a string quartet that required four people in 1800 still requires the same number of people in 2020. And so does a massage, or a medical examination, or an elementary school class. The growth in productivity in the automobile and other non-service sectors does not help make hospitals or schools more productive. But it does make them more expensive.

How?

The Hospital and the Disease

Baumol and Bower discovered that costs in some labor-intensive sectors are going up because of productivity improvements in goods-producing sectors. When, say, Toyota, figures out how to make more cars with fewer people, it ends up with fewer and more productive employees and with cars that are priced more competitively. Generally, more productive employees receive higher salaries and spend those salaries on goods such as housing and education.

When a hospital (or orchestra) hires an accountant or administrator, they compete in the same labor market as Toyota. And because Toyota has become more productive (and pays higher wages to fewer people), the hospital is now competing in a labor market where good administrators and accountants expect higher salaries.

Further, living costs increase because of general inflation and the growth in housing and education costs (resulting from rising wages in productive industries). And so, while a string quartet still requires only four people in 2020, such a quartet's operating costs are more than 20 times higher than they were in the 19th Century.

This dynamic — wage growth in industries with low or limited productivity growth — is now called Baumol’s Cost Disease. It has been used to explain the increase in the cost of a variety of in-person services and as an argument for why some services — particularly healthcare, education, and the arts — should be funded by the state and not by for-profit entities.

The disease is real, but there is room for optimism. As Alex Tabarrok and Eric Helland point out, the production of goods also suffered from limited productivity growth for thousands of years. Sewing a coat or building a carriage took about the same time in 1500 as it did five-hundred years earlier. The Industrial Revolution made good-producing sectors more productive than ever, leaving many service sectors behind. '

But progress will not end there. As Tabarrok and Helland point out, we may now be “on the verge of a service revolution brought on by robots and artificial intelligence.” I would add remote work to that list. To understand its effect, let’s go back to the singers.

Imperfect stars

Marshal made his prediction about the earning potential of singers in 1890. A few years later, phonographs (record players) became commercially available. Suddenly, “the number of persons who can be reached by a human voice” was no longer “strictly limited.” Then came the radio, talking films, and the television.

In The Economics of Superstars, Sherwin Rosen calls these “joint consumption technologies” — tools that enable a single seller to reach an unlimited number of customers at a very low (marginal) cost. These technologies introduced new benefits for consumers and new economies of scale for performers. The price of entertainment dropped since it was no longer necessary to go to Covent Garden to hear the world’s greatest singer, and it was possible to listen to the same album again and again at no extra cost. For performers (including news anchors and athletes), one hour of work in a single location could suddenly reach many people across the country and, later, the world.

But these productivity gains did not affect the entertainment industry in the same way they affected the automotive sector. When it comes to creative work, labor is not a simple input that can be increased and decreased to optimize output. In creative endeavors, one specific person can do something that many other people combined cannot do. As Rosen puts it, “hearing a succession of mediocre singers does not add up to a single outstanding performance.”

Technology made it possible for “a single outstanding performance” (and performer) to eclipse almost everything and everyone else. The result was the emergence of a handful of superstars at the top that make more money than all other performers in their field combined. Those at the bottom did not just earn less; they became redundant. In one example, Rosen notes that in 1981, the U.S. probably had less working comedians than it did a hundred years earlier, despite a fourfold increase in population and no change in the overall human appreciation for a good joke.

We mentioned that ten non-superstars could not replace the economic output of one superstar. It is also difficult to replace one superstar with another: diehard Brad Pitt fans would not watch a film if their favorite star were replaced by the equally popular (but specifically different) Tom Hanks. Rose calls this “imperfect substitution.”

Imperfect substitution explains why people would be willing to pay a high premium for something that is only marginally better. But it does not explain why all the rewards would be concentrated among a tiny group of participants. This, says Rosen, is where technology comes in. When “imperfect substitution” is combined with “joint consumption technologies,” the result is “the possibility for talented persons to command both very large markets and very large incomes.“

And indeed, by the middle of the 20th Century, popular entertainers were not just making more than Mrs. Billings did in 1801. They were making more than almost anyone else on earth. In 1958, the CEO of U.S. Steel, one of the largest companies on earth, earned $300,000 a year. Frank Sinatra earned nearly $4 million during the same year, or about $35 million when adjusted for inflation.

All humans are unique. And all employees have some specific skills and are not perfect substitutes for one another. But when the prevailing “joint consumption technology” was television or radio, only a handful of people could live up to their full potential. This held many people back, but it also protected many more people from scalable competitors. It created a world that was relatively stable for the average employee. Companies settled for less than perfect employees for most jobs because it was unreasonable to expect anything better.

The technologies of the previous era — TV, radio, film — did not just cap most individuals' potential. They also constrained the potential of whole sectors of the economy.

Code of honor

In theory, the economics of superstars apply to any knowledge work, including software development, design, and creative accounting and law. In practice, income in most sectors has been more normally distributed and did not display the type of concentration that is common in the entertainment world. How come?

Let’s start with the theory. Following my previous article on The TikTokization of Work, my friend Zach Valenta sent me this article about the bimodal distribution of income for lawyers and software developers. The article drove me into a rabbit hole of studies about wages and productivity in various industries.

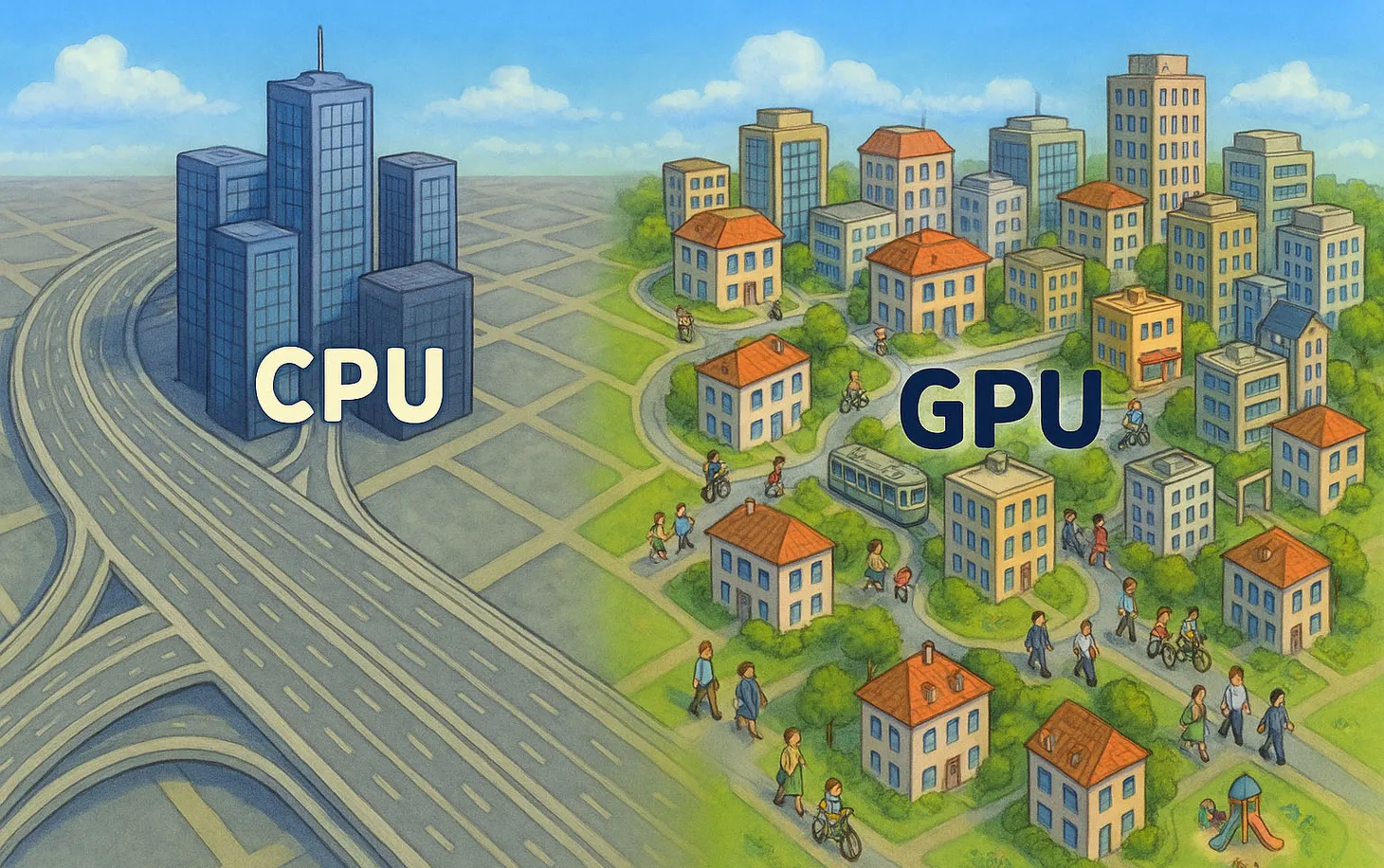

When it comes to software developers, “imperfect substitution” is strong. As Joel Spolsky points out in his analysis of superstar engineers, “the quality of the work and the amount of time spent are simply uncorrelated.” One great engineer can do in one hour what ten mediocre engineers cannot do in a day.

The notion of the 10X engineer is now a full-blown meme, but it is backed by extensive research. The idea originates from a 1968 analysis of two productivity studies focused on computer programmers. The studies revealed “large individual differences between high and low performers, often by an order of magnitude.“ The Harvard Business Review concurs that “in fields like computer programming, an eight-to-one difference between the productivity of stars and average workers has been reported.” Professor Mark Guzdial summarizes the literature on the subject here.

These performance differences are reflected in the hiring policies and actual results of the world’s most innovative companies. As the Wall Street Journal reports:

One top-notch engineer is worth "300 times or more than the average," explains Alan Eustace, a Google vice president of engineering. He says he would rather lose an entire incoming class of engineering graduates than one exceptional technologist. Many Google services, such as Gmail and Google News, were started by a single person, he says.

Following Google’s example, if an average software engineer earns about $100,000 per year, a top-notch one should earn $30,000,000, or 300 times more. This would be similar to Frank Sinatra’s income in today’s dollars. However, even Google’s own Chief Technology Officer does not make that much in salary or stock grants. And my understanding is that non-executive engineers make much less, including those who are top-notch.

If “imperfect substitution” is so high for software developers, why is their income distribution far less skewed than that of entertainers?

Because of geography. As you recall, when “imperfect substitution” is combined with “joint consumption technologies,” the result is “the possibility for talented persons to command both very large markets and very large incomes.“ While music and TV stars can be broadcast from and to anywhere, software engineers can only work in one place.

Software products can be consumed by multiple people and easily reach every corner of the planet (making owners of some software firms very rich). But software employees can only work within a reasonable distance of where they live. While the market for software products is now global, the market for on-site software employees is still local. The number of potential employers and, thus, the total income of the most productive employees is capped due to geography constraints.

The ability to work remotely changes this equation. And its impact will be compounded by several other factors.

Ten Times Ten

The internet makes it possible for many knowledge employees to work from anywhere. The earning potential of (many of) the most productive employees is no longer capped by geography. As a result, we will see the emergence of a new class of people earning salaries that are an order of magnitude higher than what we saw in previous decades.

Many of these people will remain directly employed, and some will become self-employed but will work on an exclusive basis with one or a few companies. (This also ties into a separate topic about the structure of corporations, which we’ll leave to another time).

Note that I am not talking about the emergence of a handful of highly-paid superstars in the vein of Hollywood’s Brad Pitt or Tom Hanks. I am talking about micro-stars in the vein of TikTok’s Charli D’Amelio: a whole new layer of professionals than earn incomes that are a level below the biggest earners on in their field, but still much higher than what the average employee (or singer, or dancer) could earn in the pre-internet era.

I call this new layer of professionals the 10X Class. Several other trends support their emergence. As machines take up more of our repetitive and predictable tasks, the value of human creativity goes up. Concurrently, creative people can use technology to streamline routine tasks and focus only on what they do best — thus multiplying their own productivity. And as bandwidth and technologies of presence continue to improve, the number of tasks that can be performed remotely increases. Hence, these dynamics will spread to more sectors of the economy.

As customers and employers are exposed to a growing abundance of options, their choices will become increasingly specific. In that sense, the most valuable employees are not the ones that generate more output; instead, they are the ones that generate more specific output.

To illustrate this point, consider the fact that TikTok’s Charli D’Amico is not the world’s best or most prolific singer or dancer, or video-creator. But she has a unique combination of skills and traits that make her output compelling to a specific niche. The internet makes it possible to monetize increasingly narrow niches, and it drives customers to expect solutions that are increasingly tailored to their needs and aspirations. These solutions are developed and delivered by people with the specific skills and traits that matter to that niche.

(As an aside: This is also why we will see more and more companies choosing employees based on increasingly specific skills and traits, not just professional traits, but also personal ones such as values, political views, gender, ethnicity, and more. Likewise, we will see employees themselves self-selecting into companies based on the same considerations. But that’s a topic for another time.)

As productivity increases in some sectors, costs will rise for all sectors — as explained by Baumol’s theory. Companies that try to avoid hiring the most productive employees will see their margins erode regardless of where they are. This means that even if only some companies start hiring remotely, the dynamics will change for everyone. Ultimately, if your products are competing on a global scale, you have to compete for talent on a global scale. Previously, companies could sell globally and hire locally only because hiring globally was not an option. Now, it is.

While members of the 10X Class can work from anywhere, they still have to live somewhere. Where and how they live will have a big impact on everyone else.

The Dark Side of the Star

As I mentioned in a previous piece, cities are agglomerations of different classes of people. For each high-paying creative job, there are about five low-paying service jobs. People from different backgrounds and classes tolerate (or enjoy) each other’s company because they have to: High-income folk need access to services, and low-income folk need access to service jobs. The latter also aspire to move up economically by living in proximity to better-paid people.

A growing number of high-paying jobs are no longer dependent on location. Many high-paid employees will still choose to live in cities, but they will no longer have to. This will give them the power to move to new places or to impose their will on the places they’re already in. Members of the 10X Class will have particular power since they will have an oversized impact on the city’s tax base and the viability of local industries (both the ones that employ them and those that provide services to them).

The 10X Class is likely to face political resistance. After all, you can only vote once, regardless of how wealthy you are. But when you have a choice, you can also leave. Specific political entities are still constrained by geography. They can only affect those who live within its boundaries (even if they impose a tax on leaving). And so, cities who will not submit to their wishes might find themselves depleted of the world’s most productive people.

The low-income people that will be left behind will face a multitude of challenges. They will have fewer customers to serve. Their employers’ operating costs will be subject to Baumol’s cost disease, increasing the pressure to automate or shut down. And the tax base that pays for the policing and education services they consume will diminish. These consequences are troubling, and I have written about them elsewhere.

But the rise of the 10X Class will not only affect low-income people. The 10X Class’s increased productivity will make many of their own colleagues redundant. As blue-collar employees lost their manufacturing jobs once their industries became more productive, white-collar employees will lose theirs. Anyone mediocre is at risk. And by mediocre, I do not mean “not good”; I mean interchangeable, lacking unique traits, lacking very, very specific skills that make them relevant for that particular job.

In its grace, the internet will also enable many of these redundant employees to find something new to do, to find a niche where their own unique traits are without substitute. But making the most of this opportunity would require skills and mental fortitude that most white-collar employees lack. These skills and mental abilities can be acquired. How? In future articles.

P.S.

Cover illustration by Thomas Rowlandson showing singer Frederika Weichsell, mother of singer Elizabeth Billington, 1785.

This piece is part of a series about the redistribution of income from creative work — and the ensuiring prosperity and anxiety. The main idea is summarized in a short piece titled Winner Takes Most. Other pieces in the series explore the role of the internet, cryptocurrencies, incentives, interest rates, remote work, and talent:

Dror Poleg Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.